Part 4: Three Jewish Objections

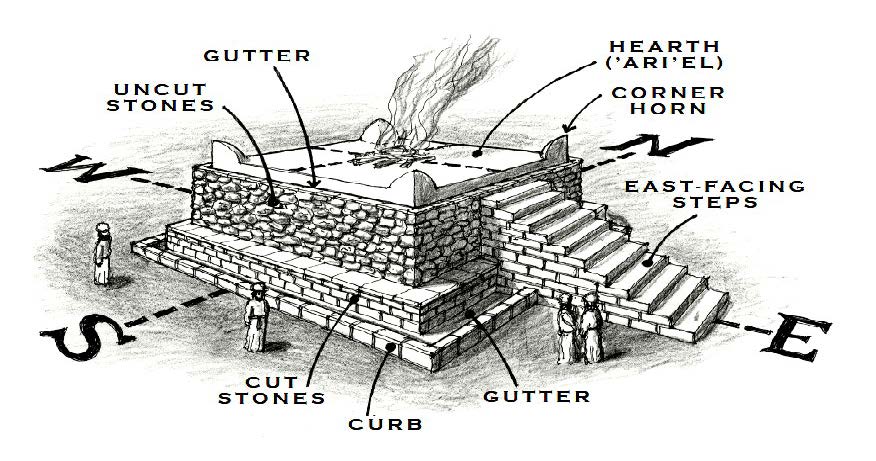

Author’s sketch of Ezekiel’s altar of burnt offering, based primarily on Block, Ezekiel, v.2, pp. 592–604. From his knowledge of the First Temple, Ezekiel might have understood it being ascended by a ramp rather than steps (Heb. uma’alotehu). From the Mishnah, Jewish commentators understand the steps or ramp to have risen toward the north, rather than the west as shown here (see p.8 in Part 2 and note). Primarily this drawing is meant to show the relationship of the altar’s four-square symmetry to that of Ezekiel’s overall temple plan (see Block, Ezekiel, v.2, pp.596–7).

* * *

THE WORD OF THE LORD came expressly unto Ezekiel...And I [saw] a great cloud...And out of the midst thereof came the likeness of four living creatures...And every one had four faces, and...four wings...[which] were joined one to another; they turned not when they went; they went every one straight forward...[Each] had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and...the face of an ox on the left side; they...also had the face of an eagle...And they went every one straight forward: whither the spirit was to go...And the likeness of the firmament upon the heads of the living creatures was as…crystal, stretched forth over their heads...I heard the noise of their wings, like the noise of great waters, as the voice of the Almighty, the voice of speech, as the voice of an host [or “the din of an army”] ... Over their heads was the likeness of a throne... [and the] appearance of a man above upon it…This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the LORD. And when I saw it, I fell on my face, and I heard a voice of one that spoke.—from Ezekiel 1.3–28

AND DAVID MY SERVANT shall be king over them; and they shall have one shepherd...I will make a covenant of peace with them; and it shall be an everlasting covenant with them...My tabernacle also shall be with them: yea, I will be their God, and they shall be my people.—from Ezekiel 37.24–27, the Haftarah to Va-yigash

SON OF MAN, show the house to the house of Israel, that they may be ashamed of their iniquities: and let them measure the pattern. And if they be ashamed of all that they have done, show them the form of the house, and the fashion thereof, and the goings out [i.e., exits] thereof, and the comings in [or entrances] thereof...—from Ezekiel 43.10–11, the Haftarah to Tetsavveh

4.0 Introduction

This concluding essay of my four-part “midrash” on Ezekiel’s Temple Vision addresses three issues often said to hinder Jewish persons from believing that their Messiah is Jesus (Yeshua)—the living Temple of God pictured by Ezekiel’s vision. Of course there are many such objections, and the Messianic scholar Michael L. Brown has an excellent series of five books [1] that address dozens in detail. I will just discuss three issues for connections they have to temple matters in my Parts 1, 2, and 3.

For those who have not seen Part 1, Lost and Found in the Temple, and Part 2, Jesus in the Temple, they explain my upbringing with hints of possible Jewishness, my teenage rejection of God and the Bible, and how I nonetheless came to be interested in Ezekiel’s Temple long before I believed in Jesus. It tells how I later came to see that temple as a “Scriptural framework” or diagram of the Person and work of the Jesus the Messiah. My Part 3, Ezekiel’s Temple and the Temple of Talmud, came about when I learned that many Orthodox Jews have a slightly different conception of Ezekiel’s plan than the Jewish one I knew, which was close to that of my Part 1. Then Part 3 goes on to compare the complexity of the Talmud with that of Ezekiel’s Temple. This present Part 4 can be read without any earlier part, but its concluding points assume some familiarity with them.

The first of the hindrances to Jewish persons believing in Jesus to be discussed here is the deplorable anti-Jewish writings of the aging Martin Luther. The 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation—commemorating Oct. 31, 1517, when Luther nailed his famous “95 Theses” to the church door in Wittenberg—occurred while I was working on Parts 1 and 2. On the great day, I got out of bed after a sleepless night at 4:30 a.m., made some hot tea, then sat at my computer till after 9 p.m. that evening, writing an essay attempting to “explain” Luther to Jewish readers. How inconvenient—even painful—it was of that anniversary to thrust itself into the middle of my trying to tell Jewish friends how Ezekiel outlines the principles of Luther’s Reformation! But conscience would not let me sweep this important issue under the rug. The section just below follows generally the outline of what I wrote that day, with numerous deletions and additions—though further reflection and study has made the task seem more daunting than ever.

After that I will discuss my other issues, those of Sunday worship on the “Christian Sabbath” in the larger part of the Christian church, and then the Trinity or Tri-Unity of God, showing how it is less outside the pale of Jewish thought than is usually asserted, and how observations from my Temple study actually support it.

4.1 Luther and Anti-Semitism

Martin Luther’s struggles to find peace with God within the discipline of monasticism are well known. He had more fasts and sleepless vigils than I could ever imagine doing, but could not find a sense that God had forgiven his sins, or that he would ever cease to be by nature a sinner. Luther finally found peace with God through his study of the New Testament book of Romans, which can hardly be considered an anti-semitic document, saying as it does in its first chapter that its gospel (“good news”) was “for the Jew first,” and then “also” for the gentile (Rom. 1:16) [2]. Its author, the apostle Paul (Shaul), had been before his conversion a strict Pharisee, a student of the great Gamaliel and a persecutor of the early Christians, and had played some part in approving the stoning of the first martyr, Stephen. When he later encountered Jesus in a powerful vision on the road to Damascus, he was on a mission to bring Jewish believers in Jesus back to Jerusalem to be dwelt with by the leaders of his sect.

Paul begins Romans with a joint indictment of both Jews and gentiles—neither of which can by nature find or obey God, he says, though the Jew has an advantage from his covenant heritage received from his forefathers. Then, in his chapters 3–5, Paul propounds his astounding doctrine of unmerited justification—having a right standing with God—through faith in Jesus and His work on the cross alone, in contrast to any attempt at self-justification on the basis of one’s “good works” or obedience to the holy law of God. What first got Luther’s attention was Paul’s verse 1:14, “As it is written, the righteous shall live by faith.” (As noted in Part 2, Paul’s quotation here of Habakkuk 2.4 in the Tanakh is said in the Talmud [BT Makkot 23b–24a] to be the essence of all 613 mitzvot.)

For Luther this was a revelation from heaven of an unsuspected manner of relating to God over and against the inadequacy of his law-keeping as a Pharisee. As Jesus said in John 5:24, anyone who simply believes in Him “does not come into judgment, but has passed from death to life.” Not will pass, but has passed, through trust in Him.

Through faith, Paul says, a sinner is right with God by judicial declaration. The righteousness of Messiah Jesus is imputed, or accounted to an unworthy sinner, just as Abraham was accounted as righteous by God before he was circumcised in obedience—like when the high priest Joshua had his filthy garments replaced by God with rich robes and diadem when He sovereignly removed his sin (Zechariah 3.4). Jesus bore all of God’s wrath at Paul’s sins, and Luther’s and mine, on the cross. Paul admitted he was a great sinner—even the “chief” of them (1 Tim. 1:15)—and I am a sinner (the tiniest hint was recounted in Part 1), and so was Luther, our principal subject at hand. But now when God looks at Luther (or Paul, or me) He sees the perfect righteousness of Jesus.

To relate this to the layout of Ezekiel’s Temple (Parts 1, 2), my salvation has two axes. I am justified, or declared right with God through His unmerited, undeserved grace, received simply by faith, which is itself not something I “work up” within myself, but the gift of God. All that is God’s sovereign, saving work on my behalf on the east-west axis of Ezekiel’s temple. My Spirit-enabled response, having received that declarative justification, is to follow Jesus on the north-south axis, laboring onward with Him from one degree of glory to another, worshiping and serving alongside other Spirit-filled brothers and sisters in the church and the world, doing works of righteousness that glorify God—knowing that it is He working in me to will and do for His good pleasure, and that He will not let me fall short of heaven ahead (Ephesians 2:8–10, Philippians 1:6, 2:12–13).

Distinguishing these two “salvation axes” of justification and sanctification (in contrast to the Roman Catholic view that the good works of sanctification form a part of one’s justification) was Luther’s chief accomplishment. In Jesus, we live on both axes, saved not by good works, but unto them (Phil. 2:10).

Paul’s message in Romans is the core of Luther’s gospel, and became the Reformation’s battle cry of justification “by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone” without any meritorious contribution from the good works that one has done or goes on to do out of love and gratitude to God, including the performance of the commanded sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper (much less the other sacraments added by the Roman church.) Luther’s immediate motivation for his 95 Theses was to relieve the fear of temporal punishment after death (in what Catholics call Purgatory) that he saw imposed on humble Christians to raise funds for Rome to finish building St. Peter’s and for the Renaissance popes to live lavishly, offering nothing for their money but a worth-less paper “indulgence” claiming to shorten one’s time in the “purging” flames, or the time their loved ones would spend there.

Paul returns in Romans chapters 9 though 11 to his fellow Jews. The mystery of which he wrote there is continually plumbed and pondered by Christians of different viewpoints, but I think it is clear that Paul is saying the Jewish nation has not been utterly cast off by God, or the covenant promises made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob forgotten. One day, at what Paul calls “the fullness of the Gentiles,” not just small groups of Jews like Paul saw, or the scattered individuals we see today, but Jews in numbers will believe in Jesus as the Messiah—something the world will see as “life from the dead” (Rom. 11:15). This is no anti-semitic message, but one of “full inclusion” (11:12 ESV), Paul says, of the Jews in the context of their ancient covenant.

Luther initially embraced this high calling for the Jewish people. In 1519, two years after he posted his 95 Theses, he attacked an official Roman church doctrine going back to the sixth century called “The Servitude of the Jews,” writing that only “absurd theologians defend hatred for the Jews,” and lamenting how “our behavior towards them...less resembles Christians than beasts” [3]. Four years after that, in 1523, Luther wrote Jesus Christ was Born a Jew, which invoked Paul in Romans 11: “We should remember that we are but Gentiles,” Luther wrote, “while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ…[and] we must be guided in our dealings with them not by papal law but by the law of Christian love. We must receive them cordially, and permit them to trade and work with us...” [4]

Luther was calling the church to remember Paul’s teaching that the Jewish person, even if he or she may be as yet the Christian’s "enemy" with respect to the gospel, is still "beloved" for the sake of the covenants and the Patriarchs, and one day God will show them Jesus as their Messiah. Again that was written six years after he posted his 95 reformational theses on the church door. It was a full nineteen years from the 95 Theses to when Luther turned bitterly anti-semitic in his writings.

It seems obvious that one thing that affected Luther was seeing, over the course of those nineteen years, so little movement toward belief among the Jews of Germany, after his crystal clear presentation of the gospel. The way Luther ended his That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew is telling. He said, “Here I will let the matter rest for the present, until I see what I have accomplished” [5]. The reaction of German Jews over the following thirteen years to his gospel message could not have encouraged him that he had “accomplished” very much.

At this point in my 500th anniversary essay I had some paragraphs suggesting historical and personal factors that might have contributed to Luther’s change with respect to the Jews—from writing That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew to abusive, scatological, obscene tirades. But there really is no excuse. I tried to minimize the effects of his writings, which never quite called for Jews to be harmed physically. But as Robert Michael points out in his 2006 book Holy Hatred, the restrictions and expulsions Luther repeatedly advocated would necessarily lead to confrontations in which the German princes would be required—by Luther’s own concept of God’s establishment of secular authority—to quell with deadly force, as he in fact advocated against gentiles in the German Peasant Rebellion [6]. While Luther also called Roman clerics and Anabaptists “swine,” in regard to the Jews he was inflaming long-festering ethnic prejudice. And while Hitler never specifically credited Luther for contributing to his “Final Solution,” [7] there is no question Luther’s plans for restricting the freedoms of Jews or expelling them from Germany had an uncanny resemblance to some of the Nazis’ later anti-Jewish measures, and Luther’s name on them virtually assured the quiescence of the German people [8].

I deleted several paragraphs from my anniversary essay about how Germany before Hitler was rife for nationalist revival after decades of humiliating defeats, and how Hitler’s false “cross” offered them a false hope [9]. I argued that Hitler was no Lutheran, or Christian of any sort, but quite the reverse. I even suggested that if Luther had been alive four centuries later, he would have seen Hitler’s evil and aroused the German people against him. But no truth that may be in any of those arguments can make up for the harm in his writings, whatever the final tally of its impact may be. One can only lament that. I will also not mention how Luther’s associates tried to suppress them or tone them down, or various philo-semitic episodes that slowed the march toward Auschwitz—except for just one thing because it comes from “my” Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Heller’s memoir, Megilas Eivah, which (if intended to be read as literal truth) says he was spared from death, and his whole Jewish community from expulsion, by the intervention of a Catholic statesman after R. Heller had been falsely accused by a Jewish rival [10].

If Luther had not eliminated the Epistle of James from his canon of Scripture (for its superficially conflicting passage about man being justified by works, and not faith only [11]) he might have been more inclined to heed the Apostle’s warning in the very next verse how the tongue—and by extension, the pen—“setteth on fire the course of nature, and is set on fire of hell,” and that it is “an unruly evil, full of deadly poison” (James 3: 6–8). Luther seems to have been seduced by the height of his pinnacle to think that his understanding of Paul’s gospel was unique to him, though much of his insight was present before in St. Augustine and the proto-reformer Jan Hus, and would later be discovered by the Jansenists in France. Luther’s speaking of what he “accomplished” shows him taking his eyes too much off of God; his own Pauline doctrine shows that imparting saving faith is not something man can “accomplish”—it being “the gift of God” lest anyone boast (Eph. 2:8–9), and in the case of the Jews specifically requires God’s sovereign removal of a “veil” from their eyes (1 Cor. 8:6, Rom. 11:25ff.)

Satan could not stop Luther from nailing the first blows of long-needed reformation on that Wittenberg church door, or prevent his principles from spreading throughout Germany by means of the recently invented printing press, but he could find his own way to make use of those same presses. Satan is always trying to attack God’s productive servants and exploit their failures. Consider the costly sins committed in their maturity by Noah (drunkenness), Moses (striking the rock), Aaron (casting the golden calf), David (numbering the people), Solomon (building high places for foreign gods), and Hezekiah (showing the treasures to the Babylonian envoys) that had grievous results not only for themselves, but for all of Israel. Some 70,000 innocent Israelites died from David’s “numbering” sin in 2 Sam. 24. The whole 70-year captivity of Judah in Babylon resulted from the willful sins of “godly” Solomon, “godly” Hezekiah (2 Kings 20), and Manasseh (whom one hesitates to call “godly,” except that even he apparently repented after his idolatries and had a good influence on his grandson Josiah—see 2 Kings 21, Jer. 15.4, and 2 Chron. 34 [12].)

In 1 Chron. 21, a satanic influence to which David yielded is said to have been involved in his numbering the people. Can one read the Psalms of David or the wisdom literature of Solomon without thinking of the follies of their authors? The prominence to which God elevates leaders like David and Solomon (and Luther) can be a snare, reminding Christians that God puts the treasure of His gospel into “clay vessels,” that He would get the glory, not man (2 Cor. 4:7).

With some reluctance I will mention an example of this that may hit closer to home for Jewish readers. During the course of writing this “midrash” I became aware of multiple serious allegations against a respected rabbi known for his biblical scholarship. I struggled whether or not to cite any of his writings here, and asked several Christian friends for advice and prayers for guidance for me. Despite the number and persuasive nature of the allegations, and unofficial reports that some rabbinic discipline has been imposed, apparently no criminal or civil charges have been filed. The distinguished publisher of this rabbi’s books still (at least as of the time of this writing) promotes them as significant works of biblical scholarship, and I have yet to find one negative editorial or customer comment in online reviews of them.

Whatever the Jewish community thinks of that rabbi as a human being, it seemingly regards him as a biblical authority whose writings are still to be taken at face value in theological discussion. (Perhaps we will avert our eyes from a person’s flaws—even loathsome, heinous ones—if their works, writings, or ideas are considered valuable enough.) I hope the rabbi is completely innocent of all allegations, but the fact that so many of them circulate in his community reminds us of our all being “clay vessels”—adding, if the case so warrants, this rabbi to the list with David, Solomon, certainly myself, perhaps you, too, dear reader—and dare I suggest it, Luther?

If we are seriously interested in weighing Luther’s legacy with regard to Jewish people, I believe two things are necessary. First we need to come to grips with the fact that not everyone will agree what “anti-semitism” is. Christians like me may want to distinguish it from disputing rabbinical teachings that discourage Jews from believing in Jesus as their Messiah—something sometimes called “anti-Judaism,” though I would rather think of myself as Pro-testant (i.e., for testifying to truth). But regardless how lovingly one may want to share with Jewish people the Good News of the gospel, some will still think of us like Nazi officers unthinkingly saying something humane to Jews on the way to the showers. Under the principle of Rabbi Emil Fackenheim’s “614th Mitzvah,” even the most irenic anti-Judaism will be viewed by some Jews as extending the work of Hitler [13].

Robert Michael’s Holy Hatred book points to numerous cases where “anti-Judaism” merged seamlessly into anti-semitism, and seemingly implies there is ultimately little difference between them [14]. Michael mentions a 1603 book by a Protestant professor who called the Talmud “confused and disorderly” [15]. I wonder, would Michael indict the respected contemporary Jewish scholars I quoted in my Part 3 as “anti-semites” for saying basically the same thing? I think the concepts of Judaism, like those of Christianity, should be fair play in the marketplace of ideas, as long as we conduct our-selves with charity and respect. Otherwise human understanding and any hope of a “meeting of the minds” is impossible.

As a Jew Himself, Jesus was hardly anti-semitic, but He sternly rebuked doctrines of the Jewish leaders of His day as being “of the devil.” The Apostle Paul, a Pharisee, spoke in the strongest terms about his Jewish contemporaries, but it was never what we would call “personal”; when he was rebuked for disrespect to the High Priest before recognizing him, he quickly apologized (Acts 23:4–5). Luther started out being “anti-Judaism” in this sense, before the personal bitterness of real anti-semitism infected him. John Calvin, the leader of “Reformed” Protestantism, seems to have been mostly “anti-Judaism” with the exception of a few Luther-like comments about specific Jewish opponents [16], but none of his theological works were anti-Jewish polemics like Luther’s.

But there is another dimension to this problem that only a miracle from God can overcome. In Matthew 23:37 (cited in Part 2) Jesus lamented over Jerusalem, yearning to protect it from harm like a mother shielding her offspring, but the same verse continues on to say, “and ye would not. Behold, your house is left unto you desolate.” Anyone who knows the Tanakh knows that judgment must eventually follow willful disobedience—in this case rejecting Israel’s divine Visitation. There is a long strand of Jewish thought recognizing God’s chastening of Israel not only in the Babylonian and Roman destructions of the city and their two temples, but even in the Holocaust itself [17]. Both Jews and Christians believe God chastens those He loves, and disciplines “every son He receives” (Hebrews 12:5–11, from Proverbs 3.11–12).

In my personal opinion, the wrath of God that Christians see as being prophesied against the Jews was delivered in the first century after Jesus’ death, extending through the Roman sieges of Jerusalem and Masada and perhaps the quelling of the Bar Kochba rebellion, but everything that has happened to the Jewish nation since then is the satanic attack prophesied in Revelation 12:13–16 [18]. Christians also have faced satanic persecutions, and from my understanding of biblical prophecy may have more—perhaps worse—ones ahead (see the following verse 12:17). Jews don’t want to hear of this dimension of the problem from Christians, but as much as we might want to sugar-coat it or wish it away, it cannot be done.

But the great news of the New Testament for Israel is that God has not forgotten His old covenant people, but has allowed all that has happened ultimately for a good purpose—that the gentiles might come to a knowledge of His glory—and when that has occurred to the full extent of God’s wise plan, the Jewish nation’s glorious turning to Jesus will indeed appear to the world “as life from the dead” (Rom. 11:15). The Jews, the “natural branches” of Paul’s “olive tree” in Romans 9–11, were broken off from it—as painful a doctrine as that is in terms of getting Jewish people to like us—but it is only temporary, in order for the gentiles to be grafted in, until the Jews are grafted back “into their own olive tree” (Rom. 11:24).

The second need I see for evaluating Luther’s legacy in regard to the Jews must be to weigh against whatever damage his reprehensible writings caused the positive contribution to the Jewish people from the Reformation that he started, especially through its off-shoot of Calvinism. Calvin and his followers built Luther’s justification by grace alone through faith alone into a constructive theological system, erecting a practical foundation for extending Luther’s Reformation into all of life. Calvin had his arguments with the rabbis of his day, and with rabbinic Judaism generally, but he had a high view of the historical Jews of the Bible and the religion of the Torah [19]. Even the contemporary Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who has publicly debated against Messianic apologists on the Messiahship of Jesus, has written of the positive contribution of Calvin to biblical interpretation, in which the Tanakh receives great respect, and its old covenant people along with it, as central to God’s redemptive plan [20]. Anti-semitism has not flourished in areas influenced by Calvinism.

One great fruit of Calvinism has been its contribution to the founding of the United States—from the Pilgrims’ first charter, the Mayflower Compact for the godly governance of a new world, down through the Constitutional establishment of the new republic [21]. Calvinism, with its bottom-up form of church governance that incorporated the laity along with clergy, provided more of a model for democratic, “We the people” civil government than the top-down episcopal models that more resembled medieval governments under kings and princes. Any accusation that an America founded on a Reformation base has been bad for Jewish people can be countered by the rows of crosses above the beaches of Normandy as evidence of the United States’ role in putting a stop to Nazi evil and preserving the Jewish nation—and, in turn, fully half of all American Jewish males served in WWII. [22].

Despite pockets of anti-semitism, “Christian” America has been a place where Jewish people have prospered and achieved great distinction [23]. As of this writing, the United States remains firmly in support of the modern State of Israel, and the U.S. and Israel—each having approximately seven million Jewish citizens—are the two centers of Jewish business, scientific, and cultural contribution to the world. Whatever may come to pass in the future, surely this is a philo-semitic (rather than anti-semitic) legacy from what Luther began in 1517. A noted Jewish radio host has said, “When Christianity in America dies, America dies” [24].

Another such post-Reformation development benefiting Jews has been the rise of capitalism in northern Europe, attributable in large degree to the “Protestant work ethic” coming from Luther’s doctrine of secular vocation—one’s “calling” by God to produce good fruit in secular pursuits, to work hard, save, and invest wisely, much as a minister is “called” to preach and serve in the church. According to the seminal 1904–5 text The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by the German sociologist and economist Max Weber, bolstered by further research by Gerhard Lenski in the 1950s, the Lutheran—and even more so, Calvinist—teaching of secular calling encouraged believers to overcome fears from centuries of medieval superstition, engage with the secular world, start businesses, trade with others, and accumulate wealth with which to make investments for the betterment of themselves and their fellow man.

Although the Reformers themselves were slow to abandon the Roman church’s resistance to charging interest, consensus gradually emerged concerning fair lending practices. As a result of this Protestant ethic, Jewish bankers and financiers were increasingly drawn out of the squalid ghettos of medieval Europe into the mainstream of modernizing society there and in America. This can hardly be called an advance of church-sponsored anti-semitism. It’s what the earlier Martin Luther called for in terms of Christians and Jews living and working together, the rightful consequence of his Reformation on the Jewish people.

Two last Reformational benefits I would mention are cultural ones, in my professional field of architecture, and my amateur one of music. The gleaming skyscrapers with glassy corner offices into which many Jewish financiers moved from the squalid ghettos are a mainly American product of modern architectural attitudes that have been both praised and attacked as expressions of Calvinism [25]. Classical music is certainly an endeavor in which Jewish composers and performers have excelled, as mentioned in Part 3. Amid a mixed climate of assimilation and anti-semitism, the nineteenth century saw the contributions of ethnically Jewish composers from Felix Mendelssohn to Max Bruch and Gustav Mahler to Arnold Schoenberg (who at various times of his life called himself Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish in religion).

But surely the consensus single greatest Classical composer, on whom all later ones have built, was J.S. Bach [26], whose principal musical impetus was writing music for the Lutheran church—Luther having placed more emphasis on music than any other religious figure. One book says that “if there had not been a Luther, there would not have been a Bach” [27]. Gustav Mahler said that “in Bach all the vital cells of music are united in the world as in God; there has never been any polyphony greater than this!” [28].

And it was the Jewish-Christian Mendelssohn, who belonged to the German Reformed (Lutheran/Calvinist) church, who ignited the European rediscovery of Bach in the nineteenth century, writing in a letter: “To think that it took a...Jew’s son to revive the greatest Christian music for the world!” [29] And so, in a sense, Luther lies behind the whole Classical tradition of Western music. If you think that an exaggeration, perhaps you will at least agree that music is an area where Luther’s legacy demonstrates good fruit. And, in fact, the musical tradition of the Bach-loving Mendelssohn (and before him Schubert) underlies much Jewish synagogue music from the early 1800s to today! [30].

In most of these things I’ve mentioned (except possibly from Luther to Bach), it can be objected that there is no single, straight-line path of causation from the German Reformer to the positive things I’ve described. However, there is no single, straight-line path of causation from Luther to the Holocaust. As Christopher Ocker’s major 2016 study of this issue concludes, Luther definitely “contributed” to the course of long established European anti-semitism, but “more as a conduit than a catalyst” [31]. I’m just saying when we try our best to assess the end result of clusters of influences and indirect effects—often strung together with other, apparently unrelated strands of history—we should weigh these things fairly, balancing one against the other.

I want to move on to Jewish objections to the “Christian Sabbath” and the Trinity, but before doing so I think a few words about a book I read while writing this last part may be illustrative. That book is Dawn or Dusk? (1961) [32] by another, much more recent Rabbi Heller, Rabbi Bernard Heller (1899–1976). Primarily a study of post-WWII Germany’s search for new directions, R. Heller’s 300-page book mentions Luther only twice. The first time, he quotes one of the Reformer’s most horrible passages, without elaboration, letting it do its own work to embed Luther within the tradition of church-sponsored anti-semitism.

But his other mention of Luther comes near the end of the book, where he explains one driving force in the rise of the Nazis—their exploitation of German reverence for authority, particularly their enchantment with Prussian militarism. In this context, Heller says, “Worthy of note is the ironic fact that in the land where Luther unfurled the banner with the inscription ‘conscience above (ecclesiastical) authority’ [that] ‘Heil Hitler’ and cheers for waving swastikas, the emblem that proclaimed that the dictates of the State and political authority transcend the promptings of conscience, succeeded in infecting the minds and souls of the majority” [33]. Paradoxically Heller here seems to be saying Luther’s gospel held an antedote to what so strongly fueled Nazism, and the German people should have listened to him more, not less!

In between those two Luther mentions, Rabbi Heller suggests ways he thinks Judaism has better answers than Christianity for Germany (and the world) to follow. Heller argues in those chapters that humble Judaism avoided the pagan “Caesarism” to which the Christian church succumbed, with its conscience-oppressing creeds; that Judaism believes in a good, generous God as opposed to the “sadistic monster” Christians find in their “Old Testament”; that Judaism teaches a “whole synthesis” of the secular and sacred realms in contrast to the false dichotomy Christianity, he says, fostered between them [34].

But Heller based his critiques on branches of Christianity other than Lutheranism and Calvinism. We’ve already seen R. Heller’s recognition that Luther was against his “Caesarism,” but in the other areas he was apparently unaware how Luther’s Reformational perspective—developed by Calvin and others up through Abraham Kuyper, and Frances Schaeffer in Heller’s time—gave solid answers to the pitfalls he enumerated [35]. Rabbi Boteach testified to Calvin’s exaltation of the Tanakh (as part of one unified Scriptures in opposition to the good God / bad God dichotomy of shallow theologians) and Calvinists have been and remain today on the front lines of recognizing the importance of the “secular” world within an integrated biblical “world-view.”

Before leaving Rabbi Bernard Heller, I must mention the rebuttal he gives to any notion (such as Robert Michael’s) that anti-Judaism and anti-semitism are ultimately indistinguishable. R. Heller says that some people are repelled by Jewish ritual just as others are by Catholics kissing hierarchical rings, and others by fundamentalist views on dancing or card playing. “No such person,” Heller says, “however lacking in magnanimity he may be, should be deemed to have anything in common with Hitler…Some Jews,” he continues, “seem to me to be making a great mistake...because they consider every criticism of Jews a recrudescence of Nazism” [36]. I appreciate that recognition.

I have both enjoyed and been humbled in working through these things and taking refuge from some very horrible realities of our fallen world in the great gospel truths of Jesus, Paul, Luther, and Calvin that have meant so much to me personally. I pray some Jewish person may come to look past, if not forgive, Luther’s grievous error, and discover the riches of his Pauline gospel of salvation that he refined and proclaimed for nineteen years before becoming besmirched with anti-semitism. That gospel truth is not precious to me just as a matter of theoretical discussion. It is a priceless thing to experience God’s Triune (anticipating our coming discussion of the Trinity) salvation—knowing Him as a loving Father, through Jesus the Son, in the assurance of the Holy Spirit.

To tie back to my overarching theme, salvation from the guilt of sin unto peace with God and eternal life is to possess the fullness of God’s temple—Jesus in you, and you in Him—which is the great message of Ezekiel, for the Jew first and also the gentile. That salvation has two Temple-axes, and distinguishing them in his day was Luther’s great insight, nearly two decades before his trouble began. To recast Rabbi Fackenheim’s 614th Mitzvah, letting the later errors of David or Solomon (or Luther) destroy their contributions would be allowing the Enemy of our souls to win. We are justified, declared right with God through the free gift of His unmerited grace, received simply by faith—all being God’s sovereign, saving work for us on the east-west “I shall be their God” axis of the temple. Our Spirit-enabled response, having received that once-for-all justification, is to labor with God in our sanctification on the north-south “They shall be My people” axis from one degree of glory to another, worshiping and serving with other Spirit-filled believers, knowing all the while it is God working in us to will and do, until we reach the final realization of Ezekiel’s vision in the new heavens and new earth.

Anti-semitism was and is a real danger in our world that must be recognized, opposed, guarded against, and if discerned in ourselves (those of us who follow Jesus) confessed and repented. Jewish people are to be respected and, whenever opportunities may occur, defended and protected by Christians, whether they live in Israel, America, or anywhere in the world. But whatever you as a Jewish person think of Luther the human being, his gospel—whether you receive it from Jesus, Paul, or him—is the only one that will do a Jew or gentile any eternal good.

4.2 The Christian Sabbath

The “Christian Sabbath” on Sunday is another issue said to hinder Jewish persons from seeing Jesus as their Messiah. Jews with good reason understand the Sabbath as a “sign for all time,” or “perpetual covenant” (Ex. 31.16) that God made with Israel. In the Creation Week of Genesis 1, God worked six days and rested on the seventh, hallowing that day and commanding its observance in the fourth “word” of the Ten Commandments (Ex. 20, Deut. 5) [37]. In Ezekiel’s chapter 20 retelling of the history of Israel, God says, “I gave them my sabbaths, to be a sign between me and them, that they might know that I am the lord that sanctify them” (v. 12). Many of today’s “Messianic” Jews (who believe in Jesus) observe the Friday evening/Saturday Sabbath, but how can the larger Church worship on Sunday and claim any continuity with the religion of Israel?

To begin, Christians think of Sunday not just as the “first day” of the week, but as an “eighth day.” (If Saturday is the seventh day of a week that begins on Sunday, then the next day—the second Sunday—is an eighth day, like the second, higher do in a musical “octave.”) Several Torah observances were specified for an eighth day. Circumcision is on the eighth day. There were eighth-day sacrifices for the cleansing of a leper or from bodily discharges (Lev. 14, 15). Pentecost, the fiftieth day of Shavu’ot, is the eighth day of its final “week” (6 weeks plus 8 days = 50). The Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) [38] concludes with a “holy convocation” or “solemn assembly” on the eighth day (Shemini Atzeret), when all “servile” or “laborious” work is forbidden, a day called in Lev. 23.39 a “rest day” (ArtScoll) or one of “complete rest” (NJPS)—essentially a Sabbath [39].

Of course only a universe-shaking, Divine hallowing of an “eighth day” could justify shifting the weekly Sabbath from Saturday to Sunday. But something at least approaching that did occur when Joshua prayed and God halted the sun in its place for “a whole day” (Josh. 10.13, ArtScroll/NJPS), resulting in a unique week with one weekly Sabbath following its preceding one by eight days. Joshua means “yhvh is Salvation,” as does Jesus/Yeshua—of whom Joshua was a type in leading east-to-west over the Jordan into a Promised Land, as did Jesus in pioneering the way through death to eternal life.

The ultimate cosmic event behind the “Christian Sabbath” was Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. He was crucified on a Friday and lay all of the Sabbath in the tomb, “resting” in death from the work of His whole earthly mission, climaxed in His bloody victory over sin on the cross the day before. Proving His victory was accepted by His Father, Jesus arose on that “eighth day” Sunday morning, inaugurating a new sequence of seven days beginning that Resurrection Day. Dr. O. Palmer Robertson [40] says that Jesus’ “coming forth into new life must be understood as an event as significant as the creation of the world. By his resurrection,” Robertson continues, “a new creation occurred.” The sun didn’t stop, but the greater “Sun of righteousness” arose “with healing in its wings” (Mal. 3.20, Eng. 4:2). Before that first Resurrection Day, the Sabbath was a day of holy rest. Now the Sunday “Lord’s day” is one of grateful worship and creative “resting” in the transforming, renewing, resurrection power of Jesus, which makes all things possible through the following six days of the week [41].

Robertson points out how Israel’s Sabbath rest evoked its redemption by God in the Exodus from slavery in Egypt [42]; in the second, Deuteronomy 5 giving of the commandment, Israel was told to remember their bondage in Egypt, and how God “brought thee out thence through a mighty hand and an outstretched arm: therefore the lord thy God commanded thee to keep the sabbath day” (Deut. 5.15). Believers in Jesus on their New Sabbath look back to the greater Exodus that Jesus led not from slavery in Egypt through the Red Sea to an earthly Promised Land, but from the slavery of sin through the sea of death to eternal life in a New Creation [43].

Figures 1 and 2 show how the above truths are suggested in Ezekiel’s Temple plan. The ArtScroll Ezekiel Commentary (p.716) says the sages Malbin and Radak held that Ezekiel “anticipated a new world order for Messianic times, when a new halachah would apply to the new circumstances of heightened spirituality.” Here we see that new law breaking in, in a “new covenant...not like” the old one Israel “broke” (Jer. 31.31-2).

Figure 1: The Layout of Ezekiel’s Temple

Shading indicates areas not clearly understood as to precise locations of walls and roofed-over areas. (In fact, although Ezekiel describes the three inner gates in detail, he does not mention a wall of any sort connecting them and separating the outer and inner courts.)

Figure 2: Layout of the East Outer Gate

The Temple’s three Outer Gates (from the exterior to the Outer Court) are identical. Steps lead up to a hallway with three small chambers on each side. The East Gate has seven steps; the numbers of steps to the North and South Outer Gates are not stated (but are presumably the same.) After passing between the three pairs of flanking chambers, one enters the Outer Court through a Vestibule.

The Temple’s three Inner Gates (from the Outer Court to the Inner Court) are also identical to each other, and to the three Outer Gates except for two things. First, they are reversed from the Outer Gates; one ascends steps from the Outer Court into a Vestibule, and then passes between the three pairs of opposite small chambers flanking the hallway. (This reversal may be seen in Figure 1 on the preceding page.) The second difference from the Outer Gates is that all three Inner Gates are said to be reached by eight steps (instead of seven).

Illustration by the author, based on commentary in Block, Ezekiel, Vol. 2.

Figure 1 shows how each pair of outer and inner gateways are reversed. Someone entering the Temple through an outer gate would first ascend seven steps, then pass through a hallway with six small chambers, three on a side, and finally exit through a larger vestibule into the Temple’s outer court. But to proceed on into the inner court, one would ascend eight steps to a vestibule (facing back toward the one just left) and then pass between the six smaller side chambers [44]. The pattern reverses from six-then-one to one-then-six, as the Sabbath changes from following to leading the other six days. And the steps to the inner gate change from seven (corresponding to a seventh-day Sabbath) to eight (suggesting an eighth-day one.) Ezekiel does not say how many steps lead up to his main, inner sanctuary—just to these ostensibly less important gates.

We know from Ezekiel 46 that these gates are important to the Temple’s meaning, but Figures 1 and 2 say nothing about Sabbaths or days of a week—until one views the gateways as covenant signs [45]. Consider the diagram of the east outer gate in Figure 2 as typifying the outer gates. The flanking side chambers were surely for the Levites to inspect for circumcision and ritual impurity, in view of God’s saying in Ezek. 44.6ff that the priests’ failure to enforce sanctity broke covenant with Him before the Captivity. Military defense can hardly be in view, with Israel living in “unwalled villages” (Ezek. 38.11), and no Temple could be protected by a wall just one rod (a mere 10.5 feet) high (40.5). As noted in Part 2, similar “casemate” gates in Israel may have been defensive, but Ezekiel’s must be for keeping covenant by enforcing ritual sanctity.

The temple gateways also evoke God’s covenant with Abraham in Genesis 15, which was inaugurated with the Ancient Near East ceremony of passing between the divided bodies of slain animals to show what would happen to a covenant party who broke it. The ArtScroll Stone Edition Tanach (p.30) says, “In those days, the partners in a covenant passed between the severed parts to symbolize their acceptance of the new pact.” The Jewish Study Bible (p.35) says, “The ritual of cutting animals in half and passing between them is found both in the Bible and in Mesopotamia ... Those walking between the pieces will be like the dead animals if they violate the covenant.” The Hebrew term for “making a covenant” is literally “cutting” it (karat) [46].

In the Genesis 15 covenant, God had Abraham bring a heifer, a goat, a ram, a turtledove, and a pigeon, and “cut” the heifer, goat, and ram “in two, down the middle,” but not the birds (which were presumably placed opposite each other.) This arrangement strongly resembles the layout of Ezekiel’s gatehouses, from its three pairs of halved animals divided by the central walkway and two birds set apart behind them. Abraham was then told that Israel would be in bondage in Egypt four hundred years but come out with great possessions, experiencing the redemption that Deuteronomy says their covenantal Sabbath was to recall. Then God went down the walkway between the divided carcasses in the form of a smoking oven and burning torch, essentially pronouncing a curse on Himself if He failed to fulfill the covenant.

Abraham merely watched this sovereign, unilateral ceremony. In Jesus, God unilaterally fulfilled His New Covenant with Israel. He was “made of a woman, made under the law” (Gal. 4:4) and was carried by Mary into (Herod’s) Temple through—in Ezekiel’s “temple pattern”—its seven-chambered east gate, symbolizing the days of Creation, to be presented to the priests (Luke 2:22). Thirty-three years later He climbed the eight steps and passed through the reversed gate, symbolizing the New Creation, into the inner court, to be nailed to its central cross to “redeem them that were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of sons” (Gal. 4:5). After “resting” in the tomb on the Sabbath, He arose from death with power on Sunday, the first (eighth) day of the week.

It was seen in Parts 1 and 2 how Ezekiel’s Prince occupied at times the two vestibules of these gatehouses, facing each other across the outer court, and traveled between them. But he never passed through either gate (not being the Messiah or a Temple priest). He was more like John the Baptist, who was greater than the old covenant prophets (Matt. 9:9) but less than anyone in the New Covenant who passes, simply by believing in Jesus, on through the inner gate into the New Creation (Matt. 9:11). But Jesus, in passing through both gates first fulfilled, by His perfect obedience, the whole Torah, and then paid with His blood the price for His people’s covenant disobedience, taking on Himself as Lamb of God the covenant curse represented by the slain animals. God “made him to be sin for us...that we might be made the righteousness of God in him” (2 Cor. 5:21). Thus Jesus inaugurated that New Covenant, unilaterally “cutting” it for millions as the “first-born from the dead, that in all things”—including the Sabbath—“he might be preeminent” (Col. 1:18), the “Lord even of the Sabbath day” (Matt. 12:8).

On the Temple’s north-south axis, Jesus’ redeemed people follow Him in passing through the gates, not as participants in the “cutting” of the New Covenant, but because they are “in Christ,” and “a new creation” (2 Cor. 5:17), and follow their Master wherever He goes. He unilaterally fulfilled for them all that circumcision and the Sabbath represented, and is the “substance” of which the forms of the law were a “shadow” (Col. 2:16–17). Those who follow Him up the eight steps and through the inner gate into His invisible church come to know the spiritual rest that Jesus bought them, today in a heavenly foretaste in the eighth day New Sabbath, and tomorrow in the eternal Sabbath rest of the new heavens and earth (Heb. 4:9). Those not privileged to enter the inner court—those who are merely externally baptized—remain in the outer court of the visible church in a condition not too unlike the merely externally circumcised Israelites under the old covenant. We plead with Jews and “nominal” Christians who have never been “born again” (John 3:16), do not die in your sins! Come today by faith into the invisible church of the first-born from the dead, and experience the rest only Jesus gives, now and eternally. “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart; and you shall find rest unto your souls” (Matt. 11:28–9).

The Abrahamic covenant inaugurated when God passed through the divided animals was for Jews and all the nations of the earth—peoples more numerous than the stars on a clear near-eastern night (Gen. 15.5). It was a covenant based on faith, like the essence of the 613 Mitzvot in Makkot 23b-24a: “the righteous one shall live by his faith” (Hab. 2.4), or his “faithfulness,” in that true faith always acts. But faith is the key. Abraham was justified by God, and accounted righteous in His sight because he “believed God” (Gen. 15.6), before being circumcised (Gen. 17.10), or fulfilling any of the law’s demands. Jewish friend, whether your conscience leads you to worship on Saturday or Sunday, believe in Jesus today, and experience His fulfillment of God’s righteous law on your behalf. Then you will know the Sabbath rest of Jesus, Paul, Luther—and Abraham.

4.3 The Trinity, or Tri-Unity of God

The third Jewish objection I mentioned is the doctrine of the Trinity—One God in three Persons, the same in substance, equal in power and glory. Jesus (Yeshua) is often spoken of by believers as the “Son of God,” which He is, but He is equally “God the Son.” Part 2 showed that the “theophany” of yhvh / hashem that Ezekiel saw, in his Chapter 1 chariot vision, came to the Temple—that is, became incarnate—in the Person of Jesus, meaning that He is yhvh / hashem, while simultaneously distinguished from Him in the manner of all theophanies. And accordingly in John 1:1 in the New Testament the Logos, the pre-Incarnate Son is said to be “with God” and “was God.”

At the very beginning of the Torah in Genesis 1.1–2, where “the wind” or “spirit of God” (NJPS) or “Divine Presence” (ArtScroll) hovers or sweeps over the face of the primordial waters, is this the same Being as God Himself? And consider the biblical use of the plural where “God said, let us make man in our image” (Gen. 1.26). In opposition to the Christian trinitarian understanding, the Jewish Study Bible says this” most likely” refers to a “divine council” of angelic powers [47]. While I suppose one might imagine delegated angels suggesting for God’s approval the color scheme for some animal species, it is incredible to think He would let created beings participate fully in determining the spiritual endowment of a humanity intended to “think His thoughts after Him.” And if He were just showing kindness to His angels, magnanimously giving them an opportunity to express their thoughts about matters already decided, would He then have said the result was “created in our image?” As Ephesians 1:11 in the New Testament says, God “worketh all things after the counsel of his own will”—His own will.

If were created in the “image” of some angelic “council,” then we are at least partly answerable to created powers lower than God. Knowing how some of those powers rebelled, I would not find that prospect for my earthly or eternal destiny comforting. If any “collaboration” went into the creation of man, with his unique soul made for fellowship with God, it had to have been the collaboration of equally divine Persons, inseparably united in mind and purpose, to avoid the possibility of a “committee” result. Perhaps the idea of a God with a radically fractured will goes with some of the things mentioned above in Part 3, but whatever intellectual fascination that might provide is cold comfort when that dreaded phone call from the doctor’s office comes.

I think it’s clear in the Torah (and not absent from rabbinic tradition) that the thrust of the Shema is that Jews worship the one and only Living God alone [48], rather than a proposition about His essential nature. But with regard to the “oneness” of His essential nature, the Shema’s word for “one,” ‘echad, is also used in Genesis 2.24 for male and female joined in marriage into “one” (‘echad) flesh. Likewise for the two sticks (see Part 1) that Ezekiel joined into “one” in 37.17. And in Ex. 36.13, Moses was told to join the many components of the tabernacle together into “one whole” (‘echad). Like a married couple, the two sticks, and the tabernacle, the “oneness” of God is a compound unity.

The biblical temples, as places for God’s Presence with man, were also compound unities. Was the First or Second “Temple” a single inner sanctuary building, or a complex of courts and buildings on the Temple Mount? They were both single buildings and complexes of buildings at the same time. A priest heading for duty in the sanctuary would have said he was going to “the Temple” with a different idea in mind than a lay Israelite going to “the Temple” (i.e., the outer court) to worship. Though the configuration of courts is different, this is just as true of Ezekiel’s temple. Perhaps this makes it just a little easier to affirm the God of the temples, who expressly prescribed their “pattern” to reflect heavenly realities as also being “One” with a compound “oneness.”

The Trinity is not a “thing” that can be pictured, and these analogies are but the palest reflection of ineffable truth beyond human comprehension. But like when we describe God’s “extent” negatively—as our finite minds must—by saying He is in-finite, they argue for God’s unity being non-simple. On the other hand, we know there are precisely three divine Persons in the Godhead (not two, or ten) not through abstract reasoning, but because from Genesis 1.1 to Revelation 22:21, we read about those three Persons in great detail—and none other—and see how they manifest all that “the name of God” means [49].

Indeed God’s “name” is a compound unity consisting of the totality of all God “is.” He is who (or what) “He is” or “will be”: holy and jealous and just, yet compassionate and forgiving, “The LORD, The LORD God, merciful and gracious, longsuffering, and abundant in goodness and truth...” (Ex. 34:6)—that is, His name is the fullness of the manifold specifications of His revealed character. The temples that were shadows of the heavenly one above are compound unities because they were designed by God “for the name of yhvh” (2 Chron. 6.7, see also 2 Sam. 7.13, 2 Ki. 20.9). Of course believers in Jesus as the eternal Son of the Triune God know His beautiful name to guarantee immediate access to the Father and Holy Spirit as well [50]: “Hitherto have ye asked nothing in my name: ask, and ye shall receive, that your joy may be full” (John 16:24). He prayed to His Father to “keep them through thine own name those whom thou hast given me, that they may be one, as we are” (John 17:11b).

Late in writing this paper I acquired a book on the Kabbalistic interpretation of Ezekiel’s temple in the 18th century work Mishkney Elyon by Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato (or “Ramchal”), published by The Temple Institute of Jerusalem [51] Until now I have only mentioned the mystic tradition of Judaism very briefly in Part 3. The Back to the Sources book affirms it as having made “a very significant impact upon contemporary Jewish thought and culture” [52]. From college campuses to Hollywood celebrities, it has lent “star appeal” to Judaism in the Western world. (The temple plan illustrated in the Ramchal book does not differ enough from other Heller / ArtScroll ones discussed in Part 3 to require discussion here.)

I do not see how any Jewish person who approves that book’s relating the multiple names of God to the famous ten Sefirot (or “Emanations”) of kabbalistic doctrine can avoid concluding that God is a compound unity. Can anyone who identifies “yhvh” with the Sefirah Tiferet, “Elohim” with the Sefirah Gevurah, “Ehyeh” with Keter, “Shaddai” with Yesod, “Adonai” with Malchut, and on through the ten names and Sefirot, possibly quibble with the Christian who says God is One in Three and Three in One? Wouldn’t that be a case of the pot calling the kettle black? And in this system, yhvh (“Tiferet”)—whom Jews invoke as “The Holy One, Blessed be He”—is even identified as the “Son” of two Sefirot, Hokmah and Binah [53]!

The chapter on Kabbalah and mysticism in the Jewish Study Bible acknowledges the possible influence of Christian trinitarianism and Incarnational doctrine on that strain of Judaism. It says the Tabernacle symbolically “imparts the wisdom that the multiplicity of divine powers cohere in a unified whole, that is, God’s unity may be represented organically, as a composite of discrete elements the infinity of which denies the possibility of fixed enumeration (my italics)” [54]. Not exactly an affirmation of the Trinity (or even a sefirotic 10-ity) but hardly an attack on it as “polytheism,” either. It seems to me Jews should thoroughly denounce and purge Judaism of this doctrine before they criticize the Trinity!

The Mishkney Elyon book does seem to be on to something, however, when it speaks of a future earthly temple that will be created, it says, when the temple of God in heaven extends downward to meet our lower world. “Around it a physical structure will then be built as befits this material world, and the two structures will be joined and become one ... In other words,” it continues, “a spiritual emanation of the Temple will come down into this world from the Upper World, and around it the physical reality of the Third Temple will be built” [55]. Dear Jewish reader, Jesus came as the true Temple of God on earth. He “came down” from heaven and took up human flesh to tabernacle with us, “that in the dispensation of the fulness of times he might gather together in one all things in [Jesus], both things which are in heaven, and which are on earth” (Eph. 1:10).

As I wrap up this up, I’d like to revisit for a final time Ezekiel’s inaugural vision in Chapter 1 that was discussed in Parts 1 and 2, with its relationship to Ezekiel’s Temple summarized in Fig. 5 in Part 2. We saw how the four cherubim with their four wings and four faces (the “chariot”) carried the throne of God’s Presence into Ezekiel’s temple. We said that theophany was a “personification of the Word,” or “Memra,” or “Logos,” as the Jewish Encyclopedia called it. I’d like to survey briefly some of the principal theophanies in the Torah, to see how they are “explained” in the liberal Jewish Study Bible on the one hand, and the Orthodox ArtScroll Stone Edition Tanach on the other.

Consider first Genesis Chapter 18, where “the lord,” with two human-like companions, not only appears to Abraham and talks to him, but eats a meal (of questionable kashrut, were it not pre-Sinai) that Abraham prepares. The Jewish Study Bible [56] suggests a mythic understanding of this verse, saying that “perhaps, as in some Canaanite literature, we are to imagine a deity accompanied by his two attendants.” The ArtScroll Stone Edition [57] first says simply that “God visited Abraham,” then a little later that “these three men were actually angels in the ‘guise’ of men.” What do we conclude? Did Abraham feed “God,” a “man,” or an “angel” in human guise—or do we just dismiss the story as a rehash of a pagan myth?

Or look at Genesis 32, where Jacob wrestles with either a “man” or “God” (Elohim.) The Jewish Study Bible [58] calls Jacob’s adversary a “man” or “divine being,” noting that “in the Tanakh, God and angels can appear in human form.” It mentions a midrash that views Him as Esau’s “patron angel,” making the story a warning to Israel’s enemies that Jacob (now “Israel”) would prevail against them. The ArtScroll Stone Edition [59] cites Rashi’s view that the “man” was ultimately “Satan himself.” Quite a range of possibilities for Jacob’s opponent here—divine to satanic. Later on, in Genesis 48.16, Jacob speaks of “the Angel” who had “redeemed” him from all harm, calling on him to bless Joseph’s sons—hardly an invocation of evil. Here the ArtScroll [60] says this Angel was an “emissary” of God.

In Exodus 24.9–11, God appears to Moses and his seventy elders on Mount Sinai—“They saw the God of Israel.” He is seen above a crystalline “pavement” of sapphire, which sounds remarkably like what Ezekiel saw in his chariot vision. The Jewish Study Bible [61] says “the Bible does not deny that God is visible,” but that “later Jewish writers” like Rambam came up with the notion that He is not, and considered this passage in Exodus as not actually “seeing God,” but just an “intellectual perception” or “vision” of Him. The Orthodox Stone Edition Tanach [62] says they “saw the God of Israel” without an explanatory note of any sort.

Then there’s Exodus 33.11, where God speaks to Moses “face to face.” The Jewish Study Bible [63] note says, “Even if this is to be taken figuratively, it is incompatible with vv. 20–22”—in which God tells him that no one can “see Me and live”—“which,” it continues, “is from a different source.” (That is, the two statements are not expected to be reconcilable as one authoritative Word of God.) The ArtScroll Stone Edition [64] sees nothing remarkable per se in Moses first seeing God face to face, and then being told that is impossible—in both cases the text is creating a “simile”; in the first case Moses is seeking to “increase his understanding of God’s essence and ways”—which God allows —while the second case shows that could only be the “vague degree of knowledge” represented by God’s “back.”

Consider finally when “the angel of the lord” appears to Gideon in Judges 6. Verses 11 and 12 seem intended to say Gideon was not seeing God Himself, yet in verses 14 and 16 the Hebrew text explicitly says “the lord” spoke to him. The Jewish Study Bible [65] note says it was “the lord, as the angel of the lord,” whatever that may mean. The ArtScroll Stone Edition says nothing about this verse.

I think it is clear from these examples that Jewish exegesis is unable to explain how the transcendent God, on whom no man can look and live, nevertheless came to men in visible bodies that could sit down and chat, eat dinner, and even wrestle with ordinary humans. I know this doesn’t prove the Christian Trinity is true, and a fuller discussion of trinitarian theology is out of the question here, but consider how far seeing at least many of these theophanies as manifestations of the pre-Incarnate Word of God, the eternal Son, goes toward explaining them. To employ an argument of the third century Christian theologian Athanasius of Alexandria [66], if we grant from Psalms 16 and 33 that the Word of God fills the universe completely and in its every part—which Jewish interpreters will surely acknowledge—then there should be no reason the Word cannot specially fill any specific part of the universe, as the individual theophanies show—and then at the right time, in fulfillment of all the prophecies, fill one particular human body divinely ordained from eternity for that purpose.

I would suggest that there is a beautiful symmetry and simplicity to this situation, if you can accept it. Jesus is both the Incarnat-or of all things, and the Incarnat-ed. In the unity of the Triune Godhead, Jesus the eternal Son was present with the Father and the Spirit at the very beginning of creation in Genesis 1; citing Colossians again, “by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible… all things were created by him, and for him: and he is before all things, and in him all things consist” (Col. 1:16–17). The Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, which again is printed in the Mikra’ot Gedolot, the Bible all Rabbis read from in services, says at Genesis 1:27 that “the Word [Memra] of the lord created man” [67]. Jesus is that creative Word—who was with God, and was God.

I can only hope this discussion has shown that the Trinity is not polytheism, and not so radically alien to Judaism as is often claimed. If you find our “picture” of Jesus in Ezekiel’s temple-pattern compelling, don’t be turned away by that claim, but take some time to look further into this in the New Testament and Christian theology—preferably in a Bible believing Christian church, where you will not only hear about, but see for yourself the reality of the New Testament’s New Torah that fulfills Jeremiah 31.

I hope also that this paper has made a case for Jesus as the fulfillment of so much of the typological content of the Tanakh that Dr. Joel Rosenberg talked about. But this is not a matter of mere intellectual interest. The ministry Jesus the eternal Son received is as much better than those old types and shadows as the covenant He mediates is built on better promises for the real transformation of human lives (Heb. 8:4–7). Believers in Him come not to the terrors of Sinai, with darkness and fire and blasts of sound that made even Moses quake, but to a beautiful city—the New Jerusalem of Revelation 21–22—and innumerable angels in festal array, and redeemed souls made perfect (Heb. 12:18). When I open my old King James Bible and that feeling of dread starts to wash over me, I dispel it with the knowledge that Jesus has taken the fire of God’s wrath at my sin on the cross, and given sinful me His righteousness, with the peace and joy that flow from it.

I hope you may experience the heavenly realities Ezekiel points to in Jesus. Trust Him, and from His Word He will open treasures from unseen holy places to you. Many people think the “fullness of the gentiles” that the Apostle Paul writes about could possibly be approaching, and expect the Jewish people soon to be the marvel of the world. I hope that happens, as the eleventh chapter in Paul’s letter to the Romans seems to say. Some Christians with whom I have good fellowship may disagree, but I personally am not yet convinced that there is anything in that chapter about glorious buildings, animal sacrifices, or a Davidic kingdom—just a glorious turning of Jews from Israel or any nation then on earth to Jesus that will be like “life from the dead.”

But what God may do in the future is His business. Whatever He does with Ezekiel’s temple will be for His own glory, not the pride of man. What you do with it now is your responsibility. Its pattern was to be described to the house of Israel that they might humble themselves and repent. Do that now. Embrace Jesus the Messiah while there is time. You do not know how suddenly you may make that wrong turn into the last dead end of your maze. In Jesus you will find peace in the midst of your earthly trials, and ever increasing joy as Ezekiel’s temple opens up for you into life everlasting.

If you have not done so, I would invite you to read the three preceding parts of this “Christian midrash” on Ezekiel’s Temple Vision. Part 1, Lost and Found in the Temple, and Part 2, Jesus in the Temple, explain not only the reason from my life history that led me to Ezekiel long before I called myself a Christian—indeed having grown up with at least some “anecdotal” Jewishness in my family—but also what I believe God allowed me to discover during a lifetime of pondering Ezekiel’s temple plan. Part 3, Ezekiel’s Temple and the Temple of Talmud, came about when I noticed that Orthodox Jews view Ezekiel’s Temple slightly differently from Christians and other Jews. It explains the difference, drawing some comparisons and contrasts between the temple’s complexities and those of the Talmud, and tells why I think Jewish persons should care about the difference.

Are you a Jewish person desiring to receive Jesus (Yeshua) as your Messiah? If you are willing to acknowledge that your sins disqualify you from any hope of eternal life and that you need a Savior, and if you are willing to transfer your trust from whatever you’ve been trusting in to Jesus, and forsake your sins, then pray to God as your Heavenly Father, in Jesus’ name, asking Him to forgive you. Tell Him you believe His Son Jesus lived the only perfect Torah life and died on the cross as the spotless Lamb of God whose blood atones for your sins. Ask God to save you and fill you with His Holy Spirit. Thank Him for giving you eternal life in Jesus. Only God sees the heart. If you prayed that sincerely, then study the New Testament’s Gospel of John. Choose Life, whatever other people say! Immediately begin seeking a Bible-believing church where you can be baptized, taught the Word, and discipled by mature believers.

Some Jewish converts join Messianic congregations where some Jewish traditions are observed, and one might help you, though God’s ultimate plan is to make of the Jew and gentile “one new man” (Ephesians 2:14–18) conformed neither to Jewish nor gentile traditions, but to Jesus. Many converts from Judaism join more conventional churches that place their primary emphasis on the preaching of all the Bible, and ideally have people of many ethnic, racial, and cultural backgrounds searching the Scriptures together, united in the love of Jesus—a grounding which also can help you find how to share your distinctively Jewish background in the community of faith. No church or congregation is perfect. Maybe one that believes God’s Word needs you as a member to grow more fully into the pattern Jesus wants.

Finished reading Part 4?

Bibliography

Block, Daniel I., The Book of Ezekiel (The New International Commentary on the Old Testament series) (2 Volumes). Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1997.

Breuer, Rabbi Joseph, The Book of Yechezkel (trans. Gertrude Hirschler), N.Y. and Jerusalem: Phillip Feldheim, Inc., 1993.

Clorfene, Chaim, The Messianic Temple: Understanding Ezekiel’s Prophecy, Jerusalem: Menorah Books, 2005. Features computer-generated drawings and a colorful new model.

Davis, Joseph, Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller: Portrait of a Seventeenth Century Rabbi (Oxford and Portland, OR: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2005).

Eisemann, Rabbi Moshe, The Book of Yechezkel, 3rd Ed.: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic, and Rabbinic Sources, Brooklyn, NY: Mesoreh Publications, ArtScroll Tanach Series, 1988.

Fisch, Rabbi Dr. S[olomon], Ezekiel with Hebrew Text and English Translation with an Introduction and Commentary, London & Bournemouth: The Soncino Press, 1950. (A newer second edition of this work, slightly revised, was published in 1994.)

Greenhill, William, An Exposition of the Book of Ezekiel (orig. pub. 1645–67). Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1994.

Heller, Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman (“Tosefos Yom Tov”), The Third Beis Hamikdash,Trans. R. Eliyahu Touger. Brooklyn, NY: Moznaim Publishing, 2016. A newly translated and supplemented edition of R. Heller’s Tzuras Beis HaMikdash (“Form of the House”, 1602) which includes as a fold-out his original temple diagram, said to be published with the book for the first time in 2016. Recent commentators (Eisemann, Clorfene, etc.) who refer to the written commentary in R. Heller’s book seem unfamiliar with this fold-out.

Henning, Emil Heller III, Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework Illustrating the Covenant of Grace (Second Revised Edition). Maitland, FL: Xulon Press, 2013 (rev. 2016).

Holtz, Barry W. (Ed.), Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1984. Chapters by Jewish scholars on the Tanakh, Talmud, Midrash, Jewish Mysticism, etc.

The Jewish Study Bible, Eds. Adele Berlin and Marc Svi Brettler. Oxford and NY: O.U.P., 2004. Based on the text of the 1985 Jewish Publication Society Tanakh (NJPS).

Lipschitz, Rabbi C.U. and Dr. Neil Rosenstein, The Feast and the Fast: The Dramatic Personal Story of the Tosefos Yom Tov, NY and Jerusalem: Maznaim Publishing Corp., 1984. (Incorporates a newly translated edition of R. Yom Tov Lippman Heller’s personal memoir Megilas Eivah (ca. 1631) with supplemental biographical information and genealogical charts.)

Luzzatto, Rabbi Moshe Chaim (“Ramchal”), Secrets of the Future Temple (Mishkney Elyon), Jerusalem: The Temple Institute, 1999. A recent translation of Mishkney Elyon by R. Luzzatto (1707–47) with supplemental articles and illustrations.

Rabinowitz, Rabbi Chaim Dov, Da’ath Sofrim: Commentary to the Book of Yehezkel (trans. Zvi Faier), N.Y. and Jerusalem: R. Vagshal, 2001.

Ritmeyer, Leen, The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount of Jerusalem, Jerusalem: Carta, 2006. A masterful study of the archaeology and biblical history of the Jerusalem temples.

Rosenberg, Rabbi A.J., The Book of Ezekiel (Judaica Books of the Prophets series) (2 Vols.), NY: Judaica Press, 2000.

Steinberg, Rabbi Shalom Dov, The Third Beis HaMikdash (trans. R. Moshe Leib Miller), Jerusalem: Mosnaim Publications.

The Stone Edition Tanach (ArtScroll Series), Ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman. Brooklyn, NY: ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications, 2013. Its supplemental notes on Ezekiel cite R. Eisemann’s book (above.)

Endnotes

1.^Michael L. Brown, Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus (5 Vols. 1-4: Grand Rapids, MI: 2000-2007, Vol. 5: San Francisco: Purple Pomegranate, 2009).

2.^Certainly “for the Jew first” reflects the historical reality that the gospel was first proclaimed in Jerusalem (Acts 2) and was initially mainly Jewish until resistance led the Apostles more to the gentiles (Acts 13:46). But since Paul does not say “then for the Greeks,” but “also for the Greeks” it would seem that he did not mean Jews were now displaced from the church, but Jews and gentiles were now “upon the same footing” (Matthew Henry). Since by A.D. 57 the shift toward gentile Christians was probably already a fact, in context Paul is if anything reminding the gentiles of salvation’s roots among the Jews, in accordance with what he says about the covenants with the Fathers in 3:1-2, 9:4, 11:16-18, 11:28-9, and 15:8.

3.^https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Luther_and_antisemitism#cite_note-3

4.^https://www.uni-due/collcart/es/sem/s6/txt09_1.htm

5.^Ibid.

6.^Jaroslav J. Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, Luther’s Works, 55 Vols. (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia, Fortress Press, 1955-86), V. 46: 50-1.

7.^Robert Michael, Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism,and the Holocaust (NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006) p.119. Paul Hasall notes that the Nazis imprisoned and killed even ethnically Jewish people who had converted to Christianity, whom Luther presumably would have embraced (https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Luther_and_antisemitism#cite_note-45).

8.^See Michael, Holy Hatred, op.cit., esp. pp. 120-1.

9.^See Erwin W. Lutzer, Hitler’s Cross (Chicago, Moody Press, 1995), pp. 12, 101-4.

10.^Rabbi C.U. Lipschitz and Dr. Neil Rosenstein, The Feast and the Fast (see Bibliography), pp. 7-8, 65-73. As to the factual authenticity of Heller’s story vis-a-vis conventional “deliverance narrative,” see Joseph Davis, Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller (see Bibliography), pp. 146-150, 193-7.

11.^Luther did not attain to the current evangelical understanding that Paul and James meant slightly different things by “justification.” Paul meant justification before God, James meant justification before men—and particularly the church. Paul was concerned with how a sinner may be deemed “right” by God, James with how the church may judge persons with a verbal profession of belief in Jesus but lacking righteous works to demonstrate their salvation in a visible, public way. The key is Eph. 2:8–10, which shows that salvation—meaning being declared righteous in God’s sight—is by grace through faith alone (apart from works of righteousness, as Paul says in Romans) but the Christian will necessarily go on to do works of righteousness that God prepared for him to do before the foundation of the earth. The two are inextricably linked, yet to be distinguished.

12.^Richard D. Phillips (personal communication) conjectures this based on the relative ages of the men as given between 2 Chron. 33–34. Josiah was eight years old when he began to reign upon the death of Amon. But since Amon only ruled two years after the death of Manasseh, Josiah must have been six years old when Manasseh died. That could have been time for the humbled and repentant Manasseh to have some godly influence upon the young Josiah, who from the very start seems to have followed God with a zealous heart. The story Manasseh had to tell could have contributed to that.

13.^See Emil L. Fackenheim, “Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment,” https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/jewish-faith-and-the-holocaust-a-fragment/. I sympathize with Rabbi Fackenheim’s observation that “at Auschwitz, Jews came face to face with absolute evil.” (See note [18] below.)

14.^Michael, Holy Hatred, op.cit., pp. 11-12.

15.^Ibid., p.118 (see also p.122).

16.^See G. Sujin Pak, “John Calvin and the Jews: His Exegetical Legacy,” www.reformedinstitute.org/images/Documents/GSPak.pdf (esp. see pp. 26-8). For a statement opposing anti-semitism by a major 20th century theologian in Calvin’s tradition, see Francis A. Schaeffer, “The Fundamentalist Christian and Anti-Semitism,” http://www.pcahistory.org/documents/anti-semitism.html. For a more negative assessment of Calvin, see Michael, Holy Hatred, pp. 106-7, though Michael presupposes that anti-Judaism and anti-semitism are inseparable (see note [13]).

17.^Rabbi Fackenheim acknowledges this in his 1967 Commentary article (see note [13] above), and characterizes it as a traditional Orthodox response to be repudiated.