Part 2: Jesus in the Temple

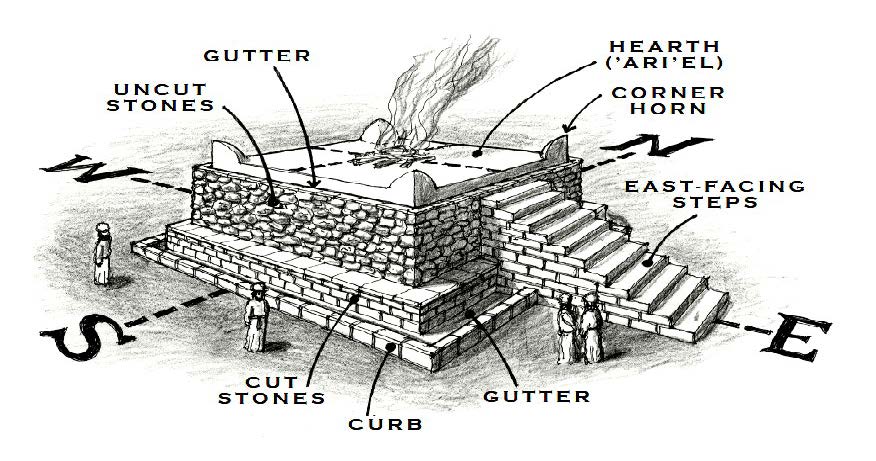

Author’s sketch of Ezekiel’s altar of burnt offering, based primarily on Block, Ezekiel, v.2, pp. 592–604. From his knowledge of the First Temple, Ezekiel might have understood it being ascended by a ramp rather than steps (Heb. uma’alotehu). From the Mishnah, Jewish commentators understand the steps or ramp to have risen toward the north, rather than the west as shown here (see p.8 in Part 2 and note). Primarily this drawing is meant to show the relationship of the altar’s four-square symmetry to that of Ezekiel’s overall temple plan (see Block, Ezekiel, v.2, pp.596–7).

* * *

THE WORD OF THE LORD came expressly unto Ezekiel...And I [saw] a great cloud...And out of the midst thereof came the likeness of four living creatures...And every one had four faces, and...four wings...[which] were joined one to another; they turned not when they went; they went every one straight forward...[Each] had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and...the face of an ox on the left side; they...also had the face of an eagle...And they went every one straight forward: whither the spirit was to go...And the likeness of the firmament upon the heads of the living creatures was as…crystal, stretched forth over their heads...I heard the noise of their wings, like the noise of great waters, as the voice of the Almighty, the voice of speech, as the voice of an host [or “the din of an army”] ... Over their heads was the likeness of a throne... [and the] appearance of a man above upon it…This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the LORD. And when I saw it, I fell on my face, and I heard a voice of one that spoke.—from Ezekiel 1.3–28

AND DAVID MY SERVANT shall be king over them; and they shall have one shepherd...I will make a covenant of peace with them; and it shall be an everlasting covenant with them...My tabernacle also shall be with them: yea, I will be their God, and they shall be my people.—from Ezekiel 37.24–27, the Haftarah to Va-yigash

SON OF MAN, show the house to the house of Israel, that they may be ashamed of their iniquities: and let them measure the pattern. And if they be ashamed of all that they have done, show them the form of the house, and the fashion thereof, and the goings out [i.e., exits] thereof, and the comings in [or entrances] thereof...—from Ezekiel 43.10–11, the Haftarah to Tetsavveh

2.0 Introduction

Those who have read Part 1 of this “Christian midrash,” entitled "Lost and Found in the Temple", are welcome to skip directly to Section 2.1, "Jesus in the Temple" below. For the benefit of persons who may not have read Part 1, or would like a brief review, I explained there my interest in Ezekiel’s vision as a Christian architect and Bible student, from my teenage discovery of it in an old King James Bible long before I was either an architect or a Christian. I told of growing up with questions of possible Jewishness from our Heller blood family—the step-name of Henning being added when my grandfather Emil Heller took his adoptive father’s name.

Despite family anecdotes about our being “German Jew” and gefilte fish being eaten in my father’s home—and people my age saying I look like Sen. Barry Goldwater—a recent Y-DNA test revealed no Ashkenazi ancestry. But that finding has not diminished my sense of identification with Ezekiel and his vision, or my burden for its importance to Jewish friends, to whom this informal “midrash” is chiefly addressed. In fact, those

leadings are stronger than ever since I found out, just in the past two years, that Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman Heller (known as the Tosefos Yom Tov for his commentary on the Mishnah) published the first volume devoted entirely to Ezekiel’s Temple in 1602, some 411 years before the first edition of my own book on it in 2013. If I am not descended from that famous rabbi, I wonder if I have not somehow inherited something of his “mantle” in terms of a passion for Ezekiel’s Temple and explaining it to others.

In Part 1, I recalled my teenage bewilderment in trying to grasp the layout of Ezekiel’s Temple alone in my bedroom, and how its maze-like aspects characterized the frustrated maze of my early life. I explained how, after receiving Jesus (Yeshua) as my personal Savior at the age of thirty in 1977, Ezekiel’s organizing scheme began clearing up for me. I know that some Jews and many Christians believe in the future physical reality of this temple, but my goal has been to provide an explanation of its “plan” or “layout,” and the arrangement of its “exits and entrances”—things Ezekiel was explicitly told in his chapter 43 to communicate to the house of Israel—in order to illuminate a meaning his temple has for today, whatever God’s plan for the future may be.

What I began noticing in the 1980s was that Ezekiel’s Temple has two crossing axes that form an organizing pattern for the themes of his text. As explained (with diagrams) in Part 1, the temple’s East-West axis contains first, the coming from the east of the Divine Presence to the temple (following its earlier departure from the First Temple as it sank into idolatry, described in Ezekiel’s chapters 8-11) and second, the flowing back out eastward of the temple’s supernatural river of grace. The North-South axis features the route of God’s worshipers, coming in from the south and exiting from the north, or vice versa. The verse saying this (Ezek. 44.9) seems inconspicuous until one considers the emphasis God places on Ezekiel’s telling Israel about the “exits and entrances,” and with the east gate permanently closed after the entry of the Divine Presence, and no gate on the west side, the north and south temple gates are its only usable exits and entrances. Ezekiel also has a priestly-kingly worship leader for Israel, the “Prince,” who enters the temple with the people, but has a special role on the East-West axis, bringing his sacrifices on behalf of them to the priests at the east gate of the inner court.

I characterized these two temple axes in terms of the two sides of God’s recurring covenant promise, “I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (for example in Ezekiel 37.27, shortly before the Temple Vision of chapters 40-48.) “I will be their God” (the E-W axis) is God’s sovereign work on behalf of His people Israel, and “They shall be my people” (the N-S axis) is God’s work in His people to make them His own. I would refer Jewish readers to the “Going Back to the Temple” section of Part 1 for details, all derived from my study of Ezekiel from Reform and Orthodox versions of the Tanakh, supplemented with rabbinic interpretations, and without referring to the Christian New Testament.

Although this Part can be read independently, I recommend going back to Part 1 to compare the corresponding diagrams of Part 2 with them, as noted on the new diagrams herein.

2.1 Jesus in the Temple

The discoveries reported in Part 1 about Ezekiel’s Temple in its original context surprised me—and more so as I began seeing its temple-pattern fulfilled in the New Testament, though I should have recalled (from the Shorter Catechism that my father tried to teach me) that there is just one Covenant of Grace from the promise in Genesis of a saving Messiah from the line of Eve all the way to Revelation, and that all prophecy speaks ultimately of Him (Matt. 5:17, Luke 24:27, John 12:41, 2 Cor. 1:20, 1 Peter 1:10-12).

On the east-west axis of God's sovereign work for man (Figure 1) is the fulfillment of Ezekiel’s multi-stage coming of God’s glory to the temple, beginning with “the dayspring” (Luke 1:78)—or “sun rising” (KJV margin)—of divine Light in the east, as in Isaiah 9.2 and Malachi 3.20 [Eng. 4:2] [1].

FIGURE 1: The East-West Axis: “I will be their God”—God’s Sovereign Acts for His People (Compare to Fig. 3 in Part 1)

The Magi (Matt. 2) followed a “star” east to west to Jesus’ manger [2]. Shepherds saw the earth light up with the arriving Glory—recall Ezekiel 43.2 (Fig. 3 of Part 1)—as “the glory of the Lord shone around them” (Luke 2:9). The angelic chorus of “Glory to God in the highest” in Luke 2 sounds like what the Targum heard—“the sound of the camp of the angels on high” [3].

Mary brought baby Jesus to the Nicanor gate at the east end of the inner court of Herod's temple (Luke 2:22), where Simeon saw the arrival of Isaiah’s “light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of [God's] people Israel” [4]. (See the plan of Herod’s Temple appended as Fig. A-1). This was the ultimate “Personification of the Word” (Logos) of God, who both was with God, and was God in the Tri-unity of the Godhead (see Part 4), coming as a man to dwell (lit., “tabernacle”) with us (John 1:1,14) [5]. The Divine Presence of Immanuel (Matt. 1:23, from Isa. 7.4) reveals the God-and-man theophanies as pre-Incarnate appearances of God the Son (see Part 4). This “God with us” carried in on Ezekiel’s chariot was the “brightness of [God’s] glory” (Heb. 1:3), and the “one mediator between God and men” (1 Tim. 2:5). As Ezekiel’s living cherubim surpassed those on the Ark, God the Son was no appearance or angel, but a living, feeling man able to sympathize with, and atone for us on the cross [6]—the Word of God in mortal flesh (John 1:14), in whom we see God and don’t die (Ex. 33.20), but live.

Shortly we will return to Jesus’ saving works for us on the east-west axis inside the inner court, but first, on the north-south axis of God's work in His people to make them His own (Figure 2), we will see Jesus the God-man dwelling with us before converging on that axis to the inner court.

FIGURE 2: The North-South Axis: “They shall be My people”—God’s work in His people to make them His own (Compare to Fig. 4 in Part 1)

For more was needful for a holy God not just to come, but to dwell with sinful man in Rabbi Fisch’s “complete sense.” Jesus had to live out perfectly, as a man, God’s holy law where Adam, Abraham, Moses, and David fell short. Alhough he was miraculously conceived in the Virgin Mary’s womb, Jesus’ otherwise normal human birth made Him a second Adam, though as the God-man He would not fail like the first. On the north-south axis He was carried south to Egypt as an infant and then north to Galilee to identify Him with the exodus of God's “son” Israel (Matt. 2:15, Hosea 11.1). In His three-year public ministry, Jesus traveled back and forth in north-south journeys between Jerusalem and Galilee, dwelling with men, sharing our burdens and temptations—yet without sin—as a “sign-act” or “acted parable” of the sort Ezekiel often performed [7], symbolically gathering, as a second David, the scattered people, or “lost sheep” of Israel into one household of God.

Speaking prophetically, the high priest Caiaphas warned the Sanhedrin in John 11:52 that Jesus would “gather into one” the children of Israel. His sign-act of the north-south trips also fulfilled Ezekiel’s joining into one of two sticks marked with the names of the divided kingdoms of Israel and Judah in 37.16 [8]. Jesus’ yearning to gather Israel shows in His lament over a resistant Jerusalem: “How often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathers her chickens under her wings” (Matt. 23:37b). The prophecies of Caiaphas and Ezekiel 37 point to the one, universal body or “temple” (Ephesians 2:11-12)—the church of believing Jews and gentiles [9] fulfilling Israel’s mission to share the knowledge of God with the nations.

In the north in His trips, Jesus the “good shepherd” of Israel (John 10:11) demonstrated human compassion in His healing miracles and, as a second Moses, in supernaturally providing food for the multitudes and spiritual manna, teaching them the essence of the Torah in His Sermon on the Mount—a second Sinai. He took His disciples still farther north, near pagan and Roman emperor shrines at Caesarea Philippi, to test His Father's work in them and build His church on Peter's confession of Him as the Anointed Messiah (Greek: Christos, Eng.: Christ) (Matt. 16:13ff). On the northern Mount of Transfiguration He actually discussed with Moses the “decease” (Gr.: exodus) He was about to perform in Jerusalem, leading His people safely through the sea of death to eternal life.

At the end of these trips Jesus turned south a last time as Israel’s Messiah to atone for sin on the cross. “When the time was come that he should be taken up, he steadfastly set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51). This “setting His face” is what God did for Ezekiel before his mission. “Ezekiel” means “God hardens,” and against the stubbornness of his hearers God made Ezekiel’s forehead “harder than flint” (Ezek. 3.9). Jesus was fully man, with feelings like Ezekiel and us, having to steel Himself against the agonies ahead that He faced from His love for unworthy sinners, daily realigning His will with the “gyroscope” of God’s unchanging Word before dawn in lonely places.

Before turning to look at the great mysteries of Jesus’ work where the temple axes converge in the inner court, we would note how Jesus’ north-south “dwelling” journeys in and among us give shape to the church He founded (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: The North-South Axis: “They shall be My people”—God’s work in His people to make them His own (Compare to Fig. 4 in Part 1)

From his priestly upbringing, Ezekiel presumably understood his complex gatehouses as places for inspecting for circumcision and ceremonial uncleanness (see Ezek. 44.4-9 for the importance God attached to this [10]), but through the covenant sign and seal of baptism, professing believers who make credible professions of faith enter the north and south outer gates of His temple as members of Jesus’ visible church [11]. In God’s inscrutable wisdom, both “wheat and tares” (Matt. 13:24) will coexist in the outer court until the final judgment. But all who truly experience the “new birth” from above witnessed in Peter’s Caesarea Philippi confession of personal faith, fulfilling the Ezek. 44 circumcision “in heart” as well as flesh, come in union with Jesus into the inner court of His invisible church, untroubled by counterfeits. True believers enter, in Messiah Jesus, the Holy of Holies itself—once just for the high priest on the Day of Atonement—in prayer and the Lord’s Supper as consecrated believer-priests (Matt. 27:51, Hebrews chs. 4, 6, 10.)

The relationship of Jesus to His church thus consummates His gathering, north-south journeys. Spiritually regenerated Jewish and gentile believers come into Him, and are transformed as He is progressively “formed” in them individually and as a new life community (Gal. 4:19). Here we see the prophesied New Covenant day when not just Moses and priests and prophets, but all the people know God intimately (Jeremiah 31. 31-34.) Ezekiel required everything about his temple and its surroundings to be most holy, and God in this New Covenant has ordained His people’s holiness from before the foundation of the world (Eph.1:4). He draws Jewish and gentile believers into practical holiness through the life-long process of sanctification (Eph. 4:24, Heb. 12:10) in which they strive against sin, mortifying it day by day in the active pursuit of a holy life, knowing it is ultimately God at work in them (Phil. 2:13, Heb. 13:21). The east gate is closed to them, but the north and south ones are wide open for Christians to go through, following in their Master’s footsteps when He dwelt among us.

Born-again believers are members of a “chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation” for God’s “own possession” (1 Peter 2:9 ESV). Jews know this as God’s calling for Israel in Exodus 19.5-6, now embracing gentiles. Isaiah 66 foretold of “priests and Levites” being ordained from gentile nations like Lud and Tubal (Asia Minor) and Javan (Greece) to be reached when God would draw all people to Himself. The Jewish Study Bible acknowledges this ordination of gentile priests as a possible interpretation of the passage [12]—as “radical,” it says, a “departure from the Torah as that sounds.” The book of Acts chronicles that happening as Paul’s missionary journeys to those very areas of Asia Minor and Greece spawned a gentile generation of Christian believer-priests.

The ArtScroll Tanach Series Ezekiel commentary says “the time will come when it is possible for God to tend His sheep through the agency of a human shepherd” [13]. It continues that just as David was taken from tending literal sheep to tending Israel, so “his descendant, the Messiah” will one day shepherd God’s people. The great Jewish commentator Maimonides (or “Rambam”) said that in addition to emphasizing God’s law, the things that would really establish a man as the Messiah would be that He would build God’s temple in its place and gather the dispersed of Israel [14]. These past pages have shown those things are what Jesus has done, and is still doing today.

FIGURE 4: Ezekiel’s New Division of the Land (Drawing by the author, based primarily on exposition in D.I. Block, Ezekiel, Vol. 2, pp. 710ff, 733)

This shows that He saves tribes (and churches and persons) individually, just as He sends them out individually as ambassadors to the world. But each tribe is also joined to the others along King Jesus’ north-south pathway of worship and service, as Paul calls local churches and their members to “stand fast in one spirit, with one mind striving together for the faith of the gospel” (Phil. 1:27).

Hebrews 8:13 says “radical departures from the Torah” like these made the Old Covenant mediated by temples and priests obsolete and “ready to pass away.” Jesus has filled Ezekiel’s temple of “God with us” in Rabbi Fisch’s “complete sense.” As He told the Samaritan woman at the well, “the hour is coming when you shall neither [at Mt. Gerizim, the Samaritans’ holy place] nor in Jerusalem worship the Father. You worship you know not what; we know what we worship, for salvation is of the Jews. But the hour comes, and now is, when the true worshipers shall worship the Father in spirit and in truth” (John 4:21-23).

Solomon (2 Chronicles 6) acknowledged that his magnificent temple was just a place-holder through which the people really prayed to God’s heavenly dwelling place, which came down to touch the earth in Jesus, the living Temple of God. Jews and gentiles, justified forever on the east-west axis of God’s sovereign acts for them, and progressively sanctified through the power of Jesus in them on the north-south axis, are joined together into a “holy temple in the Lord” built on the foundation of prophets like Ezekiel, with Jesus, ”the stone the builders rejected” (Acts 4:11 ESV, from Ps. 118.22) as its “chief corner[stone]” (Eph. 2:20-21).

2.2 Jesus in the Inner Court

We have seen so far in this section how Jesus came from the prophetic east in mortal flesh—the embodiment of what Ezekiel saw in his chapters 1 and 43. On the north south axis we’ve seen how He lived the one life of perfect Torah obedience, qualifying Him as Israel’s Messiah, and gatherer of Israel, and the righteous Branch from Jesse’s stem who would build upon Himself a spiritual temple of Jews and gentiles. Like the change of perspective in 43.5 that enabled Ezekiel to see God’s glory filling the inner parts of the temple, this background prepares us to understand what Jesus accomplished in the inner court that made His church-temple of believing Jews and gentiles possible.

Ezekiel’s Prince came as close to entering that court as its east inner gate, though his north-south and east-west roles prefigure Jesus the Messiah in his movements on both axes. But far beyond that Prince, Jesus the Son of David (Matt. 1:6-16) and King of kings (Rev. 19:16) both came in through the east outer gate, and went on into the inner court, not as a Levitical priest, which He was not, but as a priest of the older (indeed eternal) order of Melchizedek (Ps.110, Heb. 5, 7). Aaron’s priestly line paid homage to Him through Abraham in Genesis 14, when as yet unborn in his loins [17]. Jesus thus expanded the kingly-priestly role of Ezekiel’s “Prince” [18] outward and inward, from the outer gate to the central cross, where God’s saving works for man in Jesus and in man in Jesus converge. We are saved by His death and His life (Rom. 5:10); He took a mortal body both to live out the Torah’s righteous demands and condemn sin in our flesh (Rom. 8:2-3). In Him we “die to sin and live to righteousness” (1 Pet. 2:24 ESV). We are crucified with Him, and live in Him, and He in us (John 15:5, Gal. 2:20, Eph. 1:3).

I gather that apart from some minor skirmishes with idolatry and yetzer hara’, most Jews think that since consecrating themselves to God at Sinai neither their nation nor they individually have what Christians call a “sin problem,” or need a Savior like Jesus. If they think about a future Messiah, it’s not in those terms. I delayed this aspect till after the north-south dwelling, gathering, Temple-building ones because those are closer to Jewish understandings of Messiahship, and build a platform for the sin-atoning aspect. Only God alone through His Word can tell you anything concerning personal sin, but I offer now for your consideration that Jesus provides the only explanation for why the sacrificial system is in the Bible [19]—and what Ezekiel’s strange Temple Vision means.

Mary had carried Jesus as a baby to the entrance of the inner court, but at the climax of His public ministry He was finally to enter it on Palm Sunday, when He descended westward from the Mount of Olives (immediately east of Jerusalem) to be nailed hand and foot to the cross five days later. The crowd’s shouting, “Blessed be the King that cometh in the name of the Lord: peace in heaven, and glory in the highest” (Luke 19:38) echoed the angelic chorus at the announcement of His birth (Luke 2:14), when God’s Glory first came to His Temple from the east. (Iain M. Duguid has pointed out how Jesus soon went back again in an “acted parable” to the same Mount of Olives, symbolically “desolating” Jerusalem by taking His holy presence from the city—recapitulating Ezekiel 11.23—directly after pronouncing His Matthew 23 lament over its coming destruction for missing its Divine visitation [20].)

Though Jesus was crucified somewhere outside the western city gate—to the “back” of the Second Temple, in accord with His rejection by the religious leaders—in Ezekiel’s Scriptural framework it was on the central, four-horned altar. Psalm 118.27 says, “Bind the festal offering to the horns of the altar with cords” (NJPS Tanakh) [21]. As host of the Last Supper in the upper room, Jesus by custom for a Passover Seder would have led His disciples in singing that final section of the Hallel—Psalms 114-118, ending with Ps. 118’s binding of the sacrifice to the altar’s horns—just before going out to pray at Gethsemane [22]. The next morning His four extremities were painfully “bound” to the “altar” of the cross with Roman nails.

According to Rambam, Ezekiel’s altar must be at the precise spot of the Akedah, where Abraham bound his beloved son Isaac with cords and laid him on an altar, ready by faith to offer him up to God as a sacrifice [23]. God stopped Abraham from killing his only, beloved son (Gen. 22.2), but did not stop evil men from binding and killing His only beloved Son (Matt. 3:17, John 3:16, Luke 9:35) for sinners like me who were His avowed enemies. Once sinners could cling to the altar’s horns for sanctuary [24], but Jesus, having “aligned” Himself in Gethsemane with the unturning chariot of God’s Word (Luke 22:42), got no reprieve. He would be bound and nailed to those horns.

Ezekiel himself had been bound with cords early in his ministry (ch. 4), when God told him to lie on one side 390 days for the sin of the Northern Kingdom of Israel and 40 days for that of Judah. The ArtScroll commentary says God intended Ezekiel as an “atonement” for Israel, in that the exiles, seeing him bound and suffering, should have repented, deflecting God’s punishment from Israel. The Talmud (BT Sanh. 39a) says God chastised Ezekiel “to wipe out the sins of Israel.” The commentary quotes the 12th-13th century Sefer Hasidim: “God’s…Justice seeks a punishment for the entire community, but is satisfied when it is meted out only to the Zaddik” (his italics).

A Zaddik(Tzadik) is said to be a righteous Jew whose merit “outweighs” his sins; Jewish tradition says there are a few alive in every age—one potentially the Messiah, if Israel “merits” His appearance [25]. Jesus’ merit outweighed His sin (there being none to weigh) while no mere man is truly “righteous” before God (Ps. 26, Ps. 143.2, Matt. 5:48, Rom. 3:23, James 2:10). The only Tzadik whose suffering could atone for Israel was Jesus, as the high priest Caiaphas testified in saying it was needful that “one man should die for the people,” rather than “the whole nation perish” (John 11:50) at the hands of Rome.

Ezekiel’s word ari’el (see p.10) for the top of his altar’s hearth (43.15) was “lion of God.” On that hearth—again quoting the NJPS Tanakh—“A pack of evil ones closes in on me, like lions [they maul] my hands and feet” (Ps. 22.17) [26]. That well describes what the hammered nails did to Jesus. (Ps. 22.14, 22 [Eng. 13, 21] underscore His crucifiers as “lions.”) One Jewish objection to Jesus’ death as the atonement for sin prophesied in Isaiah 53.10 has been that His blood was not sprinkled on an altar as specified in Leviticus for guilt and sin offerings [27]. But the Talmud (BT Yevachim 53a) says the priest would sprinkle a finger’s worth of blood on the four horns of the altar [28], and we can imagine blood dripping from Jesus’ hands and feet onto Ezekiel’s four corner horns where they were “nailed,” precisely where Ezekiel 43.20 says blood was to be sprinkled in consecrating his altar.

Many modern Jews think Isaiah’s “suffering servant” is the Jewish people (not their righteous “representative” and supreme Tzadik, the Messiah.) But in Ezekiel’s “temple pattern,” Roman “lions” made the “lion of the tribe of Judah” (Rev. 5:15) bleed on the “lion of God” hearth as a sacrifice on an altar, just as Isaiah said—“he made himself an offering for guilt” (Isa. 53.10 NJPS)—in a more compelling way than a people could do. As Isaiah continues, “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned each one to his own way; and the LORD has laid on Him the iniquity of us all” (Isa. 53.6). As John said when Jesus came for baptism, “Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world” (John 1:29).

The steps or ramp Ezekiel saw ascending his altar even faced east to receive Jesus’ westward ascent, turned ninety degrees to those of Solomon’s or Herod’s temples, which were for ordinary priests, not the Messiah making His one final sin offering [29]. In ascending westward with the offering of Himself, Jesus was following and extending the east-to-west path of Ezekiel’s much more limited Prince when bringing his offerings on behalf of the people to the east gate of the inner court. And after His atoning work on the cross for His people’s sins (John 19:30), Jesus went—again, as their priestly “representative” (as Rabbi Fisch says), their Federal Head, the Second Adam—still farther west (in Ezekiel’s “temple pattern”) to present His blood in the heavenly Holy of Holies (Heb. 9:6-26). The whole sacrificial system and its tabernacle and temples were just “copies” (Jer. 17.12 [ArtScroll], 2 Chron. 6.18-21, Heb. 8:5) of a higher reality that is the ultimate source of Ezekiel’s pattern [30]. In His Ascension, Jesus entered “not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself...to appear in the presence of God on our behalf” (Heb. 9:24 ESV.)

In His Ascension to the Father, Jesus received “all authority” in heaven and earth (Matt. 28:18). In Ezekiel’s terms, His victory over sin on the cross dragged the evil of this world for destruction upon the mountains of Israel (Ezek. 39.1-4)—across their highest and sharpest point, the cross of Calvary—whereby the promised New Covenant and Kingdom of the Spirit was inaugurated (Col. 2:14-15). It is being worked out today, to be consummated at King Messiah’s return (Acts 4:25-28, Eph. 1:19-21, Col. 2:14-15). Rashi and Radak linked Ezekiel’s vision with Israel’s 50-year Jubilee, but Jesus applied its proclamation of sight to the blind, healing to the lame, life to the dead, canceled debt, and liberty to captives to Himself and His works (Luke 4:16-21 and 7:20-22, from Isa. 42.6-7 and 61.1) [31]. God’s glory was truly filling His temple (John 17:1).

As for Ezekiel’s wondrous river flowing back out eastward, 1 Corinthians 4:10 explains that when Moses struck the Rock in the desert, creating a life-giving stream of water, it was of the Spirit of Jesus that the people drank. Through His victory on the cross, the river of the Spirit flowed outward from the water and blood of His spear-pierced side (John 19:34). It’s not in Ezekiel’s vision, but the Mishnah says the Second Temple’s altar had two holes in its base through which blood from the sacrificed animals was flushed down a pipe to “mingle with the water” of a stream that flowed underneath the temple platform and out into the Kidron valley [32].

The power in Jesus’ shed blood and the water of the Spirit flowed out through the ministry of the Apostles, bringing spiritual life to the desert of a dry world. It flows today, widening as it goes, through the preaching of the life-giving gospel, the “Good News” of the free gift of eternal life in Jesus in every land, and the healing balm of the works and words of Spirit-filled Christians (John 7:38). Jesus said that from their hearts “will flow rivers of living water” (John 7:38). In the words of a hymn of Frances Havergal, “Like a river glorious is God’s perfect peace, over all victorious in its bright increase; perfect yet it floweth, fuller every day, perfect, yet it groweth deeper all the way.”

2.3 Jesus the Cornerstone

We said that Jesus, the “stone the builders rejected” in Ps. 118, was made by God the “chief corner[stone]” of His spiritual temple. The corresponding Greek word in Ephesians 2 (and also in 1 Peter 2:6) might apply to a traditional cornerstone with a date on it, at the base of a building—or otherwise to something higher up, a “capstone” or “head of the corner,” as it is translated in the NIV and ESV. (In the KJV, the “stone” part of “corner[stone]” is bracketed as a translators’ interpolation of an idea not explicit in the Greek.) The Greek word gonia for “corner” at the root of this expression is also used in the New Testament for street corners and the four corners of the earth. In context it is something exalted in position that sets the standard to which all other parts of a structure are related and compared (wherever it may be.) Most buildings are based on right angles, and the root meaning of gonia seems to be the human knee, which bends in a right angle in sitting, walking, or running.

Thus Jesus the Messiah is spoken of metaphorically as a privileged “stone” in the most exalted place of the temple of His church that establishes its order—which is in this metaphor a rectilinear one. That’s not to say a church cannot be another shape, but the very notion of e-rect-ing a building evokes rect-angular order and right angles. Our e-rect posture is paralleled by our moral sense of rect-itude, what is right, up-right, and right-eous. (Think too of ortho-gonal and ortho-dox.)

Elsewhere [33] I have considered fourfold and perpendicular order in the Bible and its origin in God’s process of creation (Gen. 1.2b,10; Acts 10:11-12; Rev.7:1)—and its role in the physical instrument of Jesus’ death that make it so powerful a symbol. For the early church Fathers it captured something of the four-cornered cosmos that Jesus was holding together even as He suffered [34]. It expresses His gathering of men to Himself—as He said, “If I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all [peoples] to Myself” (John 12:32 NKJV, see also Isa. 11.12, 45.22), and consequently people come “from the east and the west, the north and the south” into His kingdom (Luke 13:29). The gospel expands outward in all directions, renewing the creation (Rom. 8:19ff), as Jesus on the cross was “reconciling all things unto himself” (Col. 1:20), and contracts inward into the “center” of the human being, renewing the mind (Rom. 12:2). Would that some Jewish reader might be “able to comprehend” with the New Covenant saints “what is the breadth, and length, and depth, and height; and to know the love of Christ [Messiah], which passeth knowledge,” and “be filled with all the fullness of God” (Eph. 3:18-19)!

Can it be accidental that the fourfold rectilinear order of this biblical metaphor of Jesus as the “corner[stone]” is also the order of Ezekiel’s temple—of its overall layout, of the chariot from Ezekiel’s ch. 1 that carried God’s glory into its inner court, and of the four-horned altar described there when when the chariot fades from the vision? Even when Ezek. 1.6 speaks of the chariot’s four-winged cherubim, the Hebrew word for “wing” there is the same as the word for the four “corners” of the earth that the temple expands upon [35]. In Part 1, I quoted the ArtScroll commentary’s observation that Ezekiel’s chariot vision (and its reoccurrences in the book) are the “links” that hold the parts of his whole “prophetic edifice” together. (The commentary even says the altar should be visualized as being in four “quarters” or “quadrants” [36]). I’d long sensed the connection, but not grasped how fundamental it is. Figure 5 is an attempt to diagram the relationship of Ezekiel’s chariot and temple visions.

FIGURE 5: The Coming of God’s Presence to His Temple fulfilled in The Coming of the Word in Mortal Flesh

The figure’s top side shows how the fourfold chariot carries the Divine Presence into Ezekiel’s temple, that movement being paralleled on the bottom side in how the pre-Incarnate Word takes on flesh as Jesus the God-Man. The left side equates the theophany Ezekiel saw on the throne with the pre-Incarnate Word; the right side equates Ezekiel’s Temple with Jesus the Living Temple, as shown in these pages. The diagram shows there is really only one Word coming to one Temple!

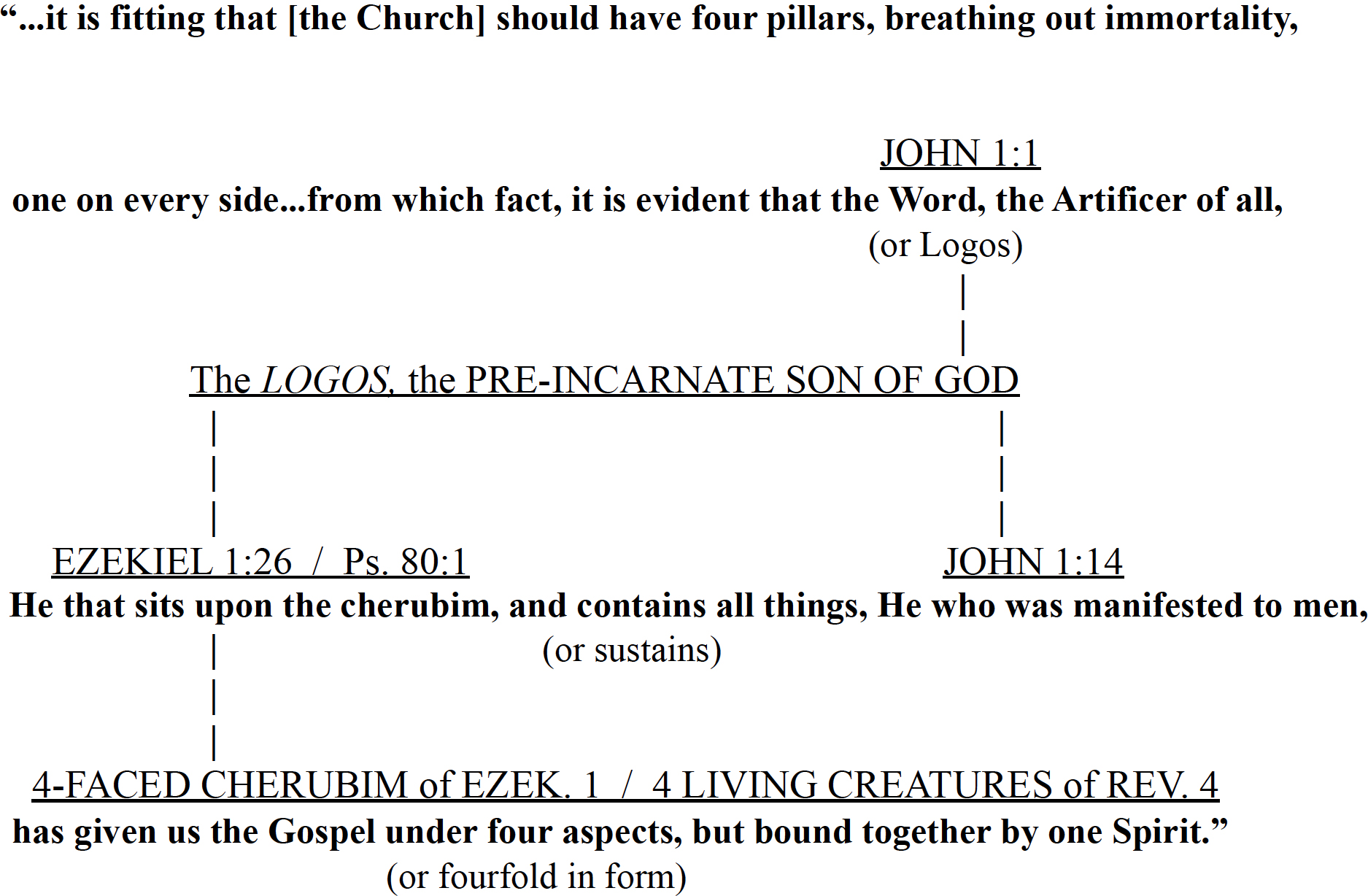

All these things are shadows of higher heavenly realities alluded to in Hebrews 8 to which the earthly temples correspond. Revelation 4 at the end of the New Testament provides a glimpse of some of those unseen realities above. Four “living creatures” surround God’s throne—”around” or “on each side of” the throne (ESV)—and each is identified with one of the four “faces” of the cherubim supporting Ezekiel’s chariot—lion, ox, man, and eagle—which have traditionally been identified with the four Gospels, which witness Jesus’ atoning sacrifice on the cross and bear, like Ezekiel’s four-faced “bearers of God’s Glory” cherubim, their report to mankind [37]. Elsewhere [38] I have suggested that the four faces of Ezekiel 1 and Revelation 4 can be harmonized, giving a consistent set of four “Gospel symbols” that reflects their organization and distinctive themes (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6: The Structure of the Four Gospels

(An attempt by the early church father Irenaeus to relate all of these themes except the overall plan of Ezekiel's Temple [39] is included as an appendix in Figure A-2. He does include the chariot.)

Elsewhere [40] I have shown how the fourfold imagery utilized in Ezekiel has been counterfeited by Satan—most immediately in pagan Rome, which nailed Jesus to its cross and persecuted His church, from the Roma quadrata myth of Rome’s founding to the quaternion that crucified Jesus and split His garments four ways, to the four-square Roman camps that Josephus describes surrounding Jerusalem before its destruction in the first century (which are still visible today surrounding the fortress of Masada.) I have looked at ways in which Ezekiel’s fourfold imagery has been distorted by people who have taken up the neo-pagan mantle I once coveted for making counterfeit temples.

I have also considered elsewhere [41] the inevitable question whether Ezekiel’s temple can and will be physically constructed one day by God or man, though I do not perceive that question as critical for seeing Jesus in the temple’s layout today, whatever God’s plan for the future may be. But let me provide just one cautionary note, which comes out of the realization in this paper of how closely Ezekiel’s chariot and temple visions are linked. If Ezekiel’s chariot vision is so holy as even to be dangerous, and to be feared, and only studied under the most guarded conditions—as it is in Jewish tradition and even to some extent in Christianity—then can one be entirely comfortable with any understanding of Ezekiel’s temple vision that reduces it to a set of “blueprints”? [42]

Many of these last things are topics for thought and discussion about which people of faith may charitably disagree, but on one thing I see no debate. When God told Ezekiel to share his vision, He did not say to tell Israel how magnificent his temple would be, or how rich its materials, or (at least in unambiguous terms) how high it would soar into the sky. He said to tell them its “pattern” or “plan” with its “goings out thereof, and the coming in thereof” (Ezek. 43.10-11)—in other words its “underlying structure” (to borrow the words of the ArtScroll Ezekiel commentary, whatever exactly it meant.) It is the “pattern” or “Scriptural framework” with its exits and entrances that is ultimately the life and work of Jesus, Immanuel, God with us, fully God and fully man, the Incarnation of God’s two-sided promise to be our God and make us His people.

Whatever God has for the future, Jesus is at home right now in the temple of His church, welcoming all Jews and gentiles who are as lost as I was in the maze of life, who are weary of their sins and weighted down by the guilt sin brings. On the one hand, Jesus' mighty acts save us. On the other, His Shepherd's hand leads us lovingly in and out of His spacious courts to eternal life.

Are you a Jewish person desiring to receive Jesus (Yeshua) as your Messiah? If you are willing to acknowledge that your sins disqualify you from any hope of eternal life and that you need a Savior, and if you are willing to transfer your trust from whatever you’ve been trusting in to Jesus, and forsake your sins, then pray to God as your Heavenly Father, in Jesus’ name, asking Him to forgive you. Tell Him you believe His Son Jesus lived the only perfect Torah life and died on the cross as the spotless Lamb of God whose blood atones for your sins. Ask God to save you and fill you with His Holy Spirit. Thank Him for giving you eternal life in Jesus. Only God sees the heart. If you prayed that sincerely, then study the New Testament’s Gospel of John. Choose Life, whatever other people say! Immediately begin seeking a Bible-believing church where you can be baptized, taught the Word, and discipled by mature believers.

Some Jewish converts join Messianic congregations where some Jewish traditions are observed, and one might help you, though God’s ultimate plan is to make of the Jew and gentile “one new man” (Ephesians 2:14-18) conformed neither to Jewish nor gentile traditions, but to Jesus. Many converts from Judaism join more conventional churches that place their primary emphasis on the preaching of all the Bible, and ideally have people of many ethnic, racial, and cultural backgrounds searching the Scriptures together, united in the love of Jesus—a grounding which also can help you find how to share your distinctively Jewish background in the community of faith. No church or congregation is perfect. Maybe one that believes God’s Word needs you as a member to grow more fully into the pattern Jesus wants.

Finished reading Part 2?

For my critique of Rabbi Heller’s 1602 plan of Ezekiel’s Temple (the basis of that in the ArtScroll Stone Edition Tanach and other Orthodox books) see Part 3 of this “Christian midrash,” Ezekiel’s Temple and the Temple of Talmud.

Appended Images

FIGURE A-1

FIGURE A-2: Irenaeus’ Linkage of the Four Gospels to Ezekiel’s Chariot

Bibliography

Block, Daniel I., The Book of Ezekiel (The New International Commentary on the Old Testament series) (2 Volumes). Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1997.

Breuer, Rabbi Joseph, The Book of Yechezkel (trans. Gertrude Hirschler), N.Y. and Jerusalem: Phillip Feldheim, Inc., 1993.

Clorfene, Chaim, The Messianic Temple: Understanding Ezekiel’s Prophecy, Jerusalem: Menorah Books, 2005. Features computer-generated drawings and a colorful new model.

Davis, Joseph, Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller: Portrait of a Seventeenth Century Rabbi (Oxford and Portland, OR: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2005).

Eisemann, Rabbi Moshe, The Book of Yechezkel, 3rd Ed.: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic, and Rabbinic Sources, Brooklyn, NY: Mesoreh Publications, ArtScroll Tanach Series, 1988.

Fisch, Rabbi Dr. S[olomon], Ezekiel with Hebrew Text and English Translation with an Introduction and Commentary, London & Bournemouth: The Soncino Press, 1950. (A newer second edition of this work, slightly revised, was published in 1994.)

Greenhill, William, An Exposition of the Book of Ezekiel (orig. pub. 1645–67). Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1994.

Heller, Rabbi Yom Tov Lippman (“Tosefos Yom Tov”), The Third Beis Hamikdash,Trans. R. Eliyahu Touger. Brooklyn, NY: Moznaim Publishing, 2016. A newly translated and supplemented edition of R. Heller’s Tzuras Beis HaMikdash (“Form of the House”, 1602) which includes as a fold-out his original temple diagram, said to be published with the book for the first time in 2016. Recent commentators (Eisemann, Clorfene, etc.) who refer to the written commentary in R. Heller’s book seem unfamiliar with this fold-out.

Henning, Emil Heller III, Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework Illustrating the Covenant of Grace (Second Revised Edition). Maitland, FL: Xulon Press, 2013 (rev. 2016).

Holtz, Barry W. (Ed.), Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1984. Chapters by Jewish scholars on the Tanakh, Talmud, Midrash, Jewish Mysticism, etc.

The Jewish Study Bible, Eds. Adele Berlin and Marc Svi Brettler. Oxford and NY: O.U.P., 2004. Based on the text of the 1985 Jewish Publication Society Tanakh (NJPS).

Lipschitz, Rabbi C.U. and Dr. Neil Rosenstein, The Feast and the Fast: The Dramatic Personal Story of the Tosefos Yom Tov, NY and Jerusalem: Maznaim Publishing Corp., 1984. (Incorporates a newly translated edition of R. Yom Tov Lippman Heller’s personal memoir Megilas Eivah (ca. 1631) with supplemental biographical information and genealogical charts.)

Luzzatto, Rabbi Moshe Chaim (“Ramchal”), Secrets of the Future Temple (Mishkney Elyon), Jerusalem: The Temple Institute, 1999. A recent translation of Mishkney Elyon by R. Luzzatto (1707–47) with supplemental articles and illustrations.

Rabinowitz, Rabbi Chaim Dov, Da’ath Sofrim: Commentary to the Book of Yehezkel (trans. Zvi Faier), N.Y. and Jerusalem: R. Vagshal, 2001.

Ritmeyer, Leen, The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount of Jerusalem, Jerusalem: Carta, 2006. A masterful study of the archaeology and biblical history of the Jerusalem temples.

Rosenberg, Rabbi A.J., The Book of Ezekiel (Judaica Books of the Prophets series) (2 Vols.), NY: Judaica Press, 2000.

Steinberg, Rabbi Shalom Dov, The Third Beis HaMikdash (trans. R. Moshe Leib Miller), Jerusalem: Mosnaim Publications.

The Stone Edition Tanach (ArtScroll Series), Ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman. Brooklyn, NY: ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications, 2013. Its supplemental notes on Ezekiel cite R. Eisemann’s book (above.)

Endnotes

1.^The Jewish Study Bible (pp.801–2) identifies the coming of the “light” in Isa. 9 primarily with King Hezekiah, but acknowledges that “most later readers (both Jewish and Christian) understood the passage to describe an ideal future ruler, i.e., the Messiah.”

2.^See Greenhill, Ezekiel, pp.790–1. Colin R. Nicholl, The Great Christ Comet: Revealing the True Star of Bethlehem, Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2015, presents an astronomical theory how the course of a comet approaching the sun, and its varying effects on the length and direction of its tail, might have alerted the Magi of the Messiah’s birth and directed their journey from east to west to honor Him.

3.^Metzudat David (R. David Altschuler) says the comparison to the sound of a torrent of rushing water is “not meant literally, but to give some idea of the crescendo accompanying the Shechinah’ return” (see R. Eisemann, p. 669). Combining that with the Targum’s “sound of the camp of angels on high,” Christians might think of the mighty choruses in Handel’s Messiah, with their ecstatic overlappings of loud sound, as at least containing some hint of the supernatural effect.

4.^For the location of the Nicanor Gate in Herod’s Temple (indicated here in Fig. A-1), see any of the books of Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer and the Biblical Archaeological Society of Washington, D.C. The Kregel Pictorial Guide: The Temple (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1996) is a colorful and inexpensive elementary introduction from a Christian perspective.

5.^See notes [24] through [27] below, and the discussion of the Divine theophanies in Part 4, Three Jewish Objections, section 4.4, "The Trinity, or Tri-unity of God".

6.^See Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho(2nd century), Chs. 126–129. Justin’s title for Ch. 128 is “The Word sent not as an inanimate power, but a Person begotten of the Father’s substance.”

7.^See R. Fisch, p.xii; Eisemann, pp. xxix–xxx, 106–110; Breuer, p.xi; Jewish Study Bible, pp. 1043, 1051, 1063, etc.; ArtScroll Stone Edition Tanach, pp. 1212–1215. “Sign-acts” of Ezekiel include the binding of his tongue, his lying on each side in bondage, pantomiming a siege of a sketched diagram of Jerusalem, cooking defiled meals over cow dung, and the death of his beloved wife, all prefiguring Israel’s loss of Jerusalem and the Temple. “Acted parables” of Jesus include the Palm Sunday ride on the colt and the symbolic cursing of the fig tree (see D.A. Carson, Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Matthew, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995, Vol. 2, pp. 437, 445).

8.^Notice how in Ps. 68.27 Zebulon (the tribe geographically including Nazareth and Cana) and Naphtali (which embraced most of Galilee) play the role of representing the whole “ten tribes.” Earlier I said that Israel’s geography plays a partial role in determining Ezekiel’s bi-axial “pattern,” but the way the Gospels highlight Jesus’ Galilee-Jerusalem trips goes beyond mere geography. His north-south “acted parable” stands out because He never (at least in His public ministry recorded in the four Gospels) traveled to the large portions of Judah south of Jerusalem, such as the important city of Hebron, for instance. Perhaps to forestall efforts to make Him “King of the Jews,” He seemingly avoided associations with the places of David’s conquests and kingdom (see 1 Sam. 30.27–31, 2 Sam. 5.1–3).

9.^While emphasizing that He came in His earthly ministry “to the lost sheep of the house of Israel,” (Matt. 15:24), Jesus nevertheless healed gentiles in the region of Tyre and Sidon, and also in the Decapolis east of the Sea of Galilee—presaging the future extension of His Kingdom to the gentiles in the ministry of His Apostles.

10.^See my Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework, pp. 55–7 for a discussion of the importance of circumcision in Ezekiel’s context and how the ta’im, or side chambers of the three outer gateways of his temple could conceivably be understood to facilitate the Levites’ inspections.

11.^One thing that might distinguish the north-south worship direction from the reverse is the possibility of sacrifices being left with the priests at the north gate of the inner court. (One might assume the text intended similar sacrifices to be left at the corresponding south gate as well, except that Lev. 1:11 also just mentions the north gate, and Ezek. 8.5 explicitly refers to it as “the altar gate” of the then defiled First Temple.) In New Covenant terms (see Fig. 3) perhaps this refers to redeemed Jews (with their historic association with sacrifices) coming in from the north, and the gentiles coming in the other way, without them. (In Ezekiel’s new tribal layout, Judah is in fact north of the temple.) The Prince comes in from north and south; Jesus gathers both Israel and His other (gentile) “fold” as well (John 10:16).

12.^Jewish Study Bible, p. 916.

13.^R. Eisemann, Yechezkel, p. 538.

14.^Hilchot Melachim 11:4.

15.^See my Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework, pp. 58–80. Iain M. Duguid, The NIV Application Commentary: Ezekiel, Grand Rapids, MI: 1999, p.548 says this part of the vision is “theology in the form of geography,” while the earlier sections were “theology in the form of architecture.” I just discovered Duguid’s book during the final preparation of this paper, but it has many excellent insights.

16.^ Iain M. Duguid, Ezekiel, Op. cit., p.544.

17.^Even Ezekiel’s priesthood does not consist simply of the line of Aaron’s sons who were qualified to minister in the First Temple, but only a subset of them, the Zadokites, who were found faithful in the time of Adonijah’s coup against David, and perhaps in later years as Judah slipped into apostasy. (See Ezek. 44.10-16.) The Christian understanding of Melchizedek’s priestly order is that it had no foundation in human history, as Aaron’s did, and its priests had no prescribed starting or ending ages for their service, and it therefore derived its authority more directly from God Himself, prefiguring Jesus’ being made a priest by God through the Spirit rather than human ordination. (See John Brown, Hebrews, Edinburgh and Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, reprinted 1994 (orig. pub. 1862), pp.322–350.)

18.^Ezekiel’s Prince differs from Messiah Jesus in that the former needed to bring an offering for his own sins (Ezek. 45.22), as well as on behalf of his people. But Jesus’ final offering for sin required Him to be “without blemish” (Ex. 12.5).

19.^In conversations I’ve had with Jewish people on the street, the claim seems to be that Jews are automatically forgiven by God—through His many promises to show mercy—as part of the special historical relationship they have with Him. But in referencing God’s declaration to Moses in Ex. 33.19 that “I shall grant grace to whom I will and shall be merciful to whom I will,” the Jewish Study Bible (p.188) well notes that “notwithstanding His gracious qualities, God remains sovereign and decides whom or whether to forgive.” Passages like Ps. 65.4 and Micah 7.18 tell how graciously God pardons sin out of His chesed, or “lovingkindness.” But chesed is only understandable in a covenant perspective, in which each side has responsibilities as well as privileges. For example, the first fourteen verses of Ps. 103 might perhaps suggest that God’s forgiveness is “automatic” for Israel, but verses 17–18 show the “Israel” David is talking about to be one that keeps God’s covenant and commandments. That doesn’t sound automatic. Are you sure you’ve done that well enough to merit forgiveness?

Again, Ps. 130.4 says with God “there is forgiveness,” but it is a “psalm of ascents” sung as Israel was going up to Jerusalem to renew covenant and sacrifice. (In the Greek Septuagint, the psalm even alludes there to the Cover of the Ark on which sacrificial blood was sprinkled.) Ps. 130 also presents God’s forgiveness in a future reference frame—He "will redeem Israel from all their iniquites” (v.8). This redemption assumes blood sacrifices, and also sounds incomplete in the present, looking forward to something yet to come—some One to come, bringing Israel’s Redemption.

And in 2 Chron. 30.18b–19, Hezekiah prays that God might pardon—”provide atonement” (NJPS) —for the sin of certain Israelites who had failed to be cleansed according to the bloody purification sacrifices of the Temple; the Jewish Study Bible (p.1812) calls that a “remarkable deviation” from the Priestly norms of ritual purity. “Sincere prayer from a righteous king,” it continues, “trumps typical concerns.” Jesus is the long-prophesied, covenant making and keeping, righteous King whose not only prayers, but direct personal intercession saves and purifies. He is God’s chesed, His covenant lovingkindness, and the final blood sacrifice that secures it. Are you relying on your teshuvah, torah obedience, and mitzvot to earn you God’s forgiveness? God sovereignly pardoned David’s great sin, but are you in David’s class with God? The wooden table Ezekiel sees in his chapter 41 inspires a passage in BT Berakhot 55a teaching that as the temple’s altar once atoned for Israel, now “a man’s table atones for him [because it gives him the opportunity to practice charity by sharing his food]” (R. Eisemann, p.650). Are you sure you’ve shared enough to deserve God’s forgiving all your sins? (I haven’t.)

20.^Iain M. Duguid, The NIV Application Commentary: Ezekiel, Grand Rapids, MI: 1999, p.153. I just discovered Duguid’s book during the final preparation of this paper, and this symbolic enactment of Jerusalem’s coming destruction is a detail I had not noticed. In terms of the Scriptural framework of my present paper, in which God cannot totally leave the spiritual Temple to which He has returned (Ezek. 43.7), that trip to the Mount of Olives was a temporary withdrawal from the city as an illustrative sign-act of the physical Temple’s coming destruction. Jesus came right back to suffer and die in, and for His spiritual temple—“I am with you always, even to the end of the age” (Matt. 28:20).

21.^The Jewish Study Bible (p.1415) suggests this was “likely the instructions for a ritual accompanying the sacrifice.”

22.^On the singing of the Hallel, see D.A. Carson, Expositor’s Bible Commentary on the NIV: Matthew (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995), Vol. 2, p.539. With regard to Jesus being crucified on Ezekiel’s altar, the Puritan commentator Wm. Greenhill in his Ezekiel commentary (p.798) says: “It had a grate, whereon the sacrifice was laid...whereby it was burnt: so Christ had a cross, whereto he was fastened and there the fire of God’s anger did fall upon him...”

23.^Rambam, Hilchos Beis HaBechirah 2:1-3. Discussion in R. Heller’s The Third Beis HaMikdash, pp. 118–9. Interestingly, the claim is that Ezekiel’s altar must sit precisely there, even if it moves the Holy of Holies from the exact spot it was located in the First or Second Temples. See also R. Moshe Eisemann, The Book of Ezekiel, p. 674. Chaim Clorfene’s The Messianic Temple, pp. 141–2 says the construction of a future temple would be predicated on locating the place of the altar in the Second Temple by digging to locate its subterranean piping system, which can only happen after the Mashiach comes and convenes a Sanhedrin. Referring to Isaac’s carrying the wood upon which he would be offered up, the Jewish Study Bible (p.46) quotes the Midrash Genesis Rabbah 56.3: “It is like a person who carries his cross on his own shoulder.”

24.^Block, Ezekiel, Vol 2, p.601.

25.^R. Moshe Eisemann, The Book of Ezekiel, p. [v] (Appendix III). In the Lipschitz and Rosenstein book The Feast and the Fast, Rabbi Heller is said to have been a Tzadik (p. 3). For the talmudic principles that the death of the righteous atones, and without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sin, see BT Moed Katan 28a, Berakhot 62b, Yoma 5a, Zeb. 6a. Speaking of Ezekiel’s six-year travail before the eyes of his countrymen, Rabbi Eisemann (pp. 106–7) says that “in horrifying graphic detail, more eloquent that words, [Ezekiel], the true son of Israel, would live through, symbolically, the terrors of the destruction and exile. Perhaps,” the rabbi continues, “in this way a path could be found to the hearts of the people.” Would that Jesus’ actual sufferings in His life of rejection by His own people and His bloody death on the cross might be a path to the hearts of the (Jewish) people today!

26.^David in Ps. 57.4 says, “My soul is in the midst of lions...the children of man, whose teeth are spears and arrows, whose tongues are sharp swords.” Translated “pierced” in LXX and some Hebrew manuscripts (so most English Bibles, often with other translations in margin.) See discussion in Michael L. Brown, Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus, Vol. 3, pp.125–6. Charles H. Spurgeon often mentioned Isa. 49.16a: “Behold, I have graven thee upon the palms of my hands” as a prophecy of Christ’s wounds—“graven” as it were by the Romans with the Jewish leaders’ assent—but only doing what God’s “purpose determined before to be done” (Acts 4:28)—and after His resurrection seen and touched by His disciples, and continuing in heaven now as the Father remembers us His children for the sake of what His Son did.

27.^Michael L. Brown, Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus, Grand Rapids, MI: 2000, Vol. 2, pp. 167–168.

28.^See Ex. 29.12. According to the Talmud, the priest would apply sacrificial blood from a bowl to each horn with the index finger of his right hand, moving it downward against the edge of the horn “until all the blood on his finger was gone” (BT Yevachim 53a).

29.^Rabbi Heller (The Third Beis HaMikdash, p.115), cites BT Zevachim 62b in defense of the rabbinic interpretation of the ramp being on the south, rather than east side of the altar. See also Rabbi Eisemann (The Book of Ezekiel, p. 680). The argument is that since the Talmud (i.e., the oral tradition) claims that priests always turned to the right, and would presumably have to turn right at the top of the ramp, they had to start out going up toward the north in order to turn eastward at the top. However, this is another case of the oral tradition—even if it is understood correctly by the rabbis, which it may not—trumping the simple meaning of Ezekiel’s words. The NJPS Tanakh, contra the Orthodox understanding, translates 43.17 to say “the ramp shall face east,” with a marginal note saying “leading up to the altar”; the explanatory note in the Jewish Study Bible (p.1127) says “the ramp faces the eastern gate.” Whichever direction these mean an ascending priest is facing, I picture the ramp being on the east side, and the priest ascending it facing west toward the sanctuary. At the top (if the Talmud is correct) he would then turn right toward the gate of the altar, where the sacrifices enter. Interestingly, the ArtScroll Stone Edition Tanach says for that verse, “[Whoever ascends] its ramp would face eastward”—in other words, it forcibly injects the rabbinic theory into the biblical text (in brackets) to change the obvious meaning of the Hebrew text. But in this case the priest turns at the top to face away from the sanctuary, something reviled as an abomination in Ezek. 8.16. See also Block, Ezekiel, Vol. 2, p.601.

30.^See BT Taanit 5a; Zohar PeKudey II, 235a; Bemidbar Rabbah 12:13 (cited in R. Luzzatto Mishkney Elyon book, pp.20–21).

31.^Matthew (12:17ff) applies the Jubilee to Jesus, from Isa. 42.1–3 on God’s servant proclaiming justice to the gentiles.

32.^Middot 3:2. See Rabbi Shalom Dov Steinberg, The Third Beis HaMikdash, p.87; Clorfene, The Messianic Temple, pp.140–142.

33.^See my Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework (Rev. 2016), pp. 16–17, 36–38. Or see my downloadable shorter article, “The Four-Fold Geometry of Ezekiel’s Temple” (in preparation). Also my Sacred Spaces: Post-Modern Architecture and the Christian’s World-View (1987, currently out of print), pp. 64–70.

34.^Melito of Sardis wrote, “He who hung the earth [in the heavens] hangs there, He who fixed the heavens is fixed there, He who made all things fast is made fast upon the tree...” Jerome likened the cross to the form of the world in its four directions. Irenaeus spoke of Christ the Logos, the eternal ceative Word, that all creation bears His imprint, and He dies on the cross epitomizing the cosmos. With special relevance to this present paper, Irenaeus decribed Jesus’ two hands, outstretched on the cross, as gathering together His two scattered peoples—Jews and gentiles—under His common headship (Against Heresies, 5.17.3–4).

35.^The common Hebrew word for “wing,” kanap(h), is derived from a root implying an extremity, and has biblical meanings including the wingtips of a bird, the ends or quarters of the earth, the pinnacle of a building, or the skirt of a garment. Psalm 18, which has been cited for its connections to Ezekiel’s chapter 1 vision, speaks in verse 11 [Eng.10] of God’s Presence riding on a cherub, on the “wings of the wind” employing a form of this word (kanpe ruach).

36.^Rabbi Eisemann, The Book of Ezekiel, p.679. The ArtScroll Stone Edition Tanach says the hearth is “square, for its four quadrants.” With the NJPS, I see no biblical support for this, the Heb. expression just meaning “square,” i.e. with four equal sides (Block, Ezekiel, Vol. 2, p.593 shows its similar usage in 40.47 and 45.1–2.) The dashed lines crossing the altar in my cover illustration for this paper were meant to show how the two crossing axes of the entire temple complex also apply to the altar; as Block (Ezekiel, Vol. 2, pp.596–7) says, the altar’s “shape is seen to match the symmetry of the temple complex as a whole.”

37.^Somewhere in my research notes I scribbled something about the fourfold gospel as a “chariot” carrying God’s saving gospel to men, and I have spent hours vainly searching Irenaeus and the related literature to see if that was their observation or an original one based on them. If I find something, I will put it in a later revision of this paper. Rabbi Eisemann (Ezekiel pp. 77,181), citing Malbim, notes that in ch.10 the four “living creatures” of ch.1 are now specifically identified as cherubim to indicate their special role as “bearers of God’s Glory” away from the First Temple to Babylon and on to the visionary Temple: “They were the bearers of the Merkavah which transported the King of Glory in exile.”

38.^See my Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework (Rev. 2016), pp. 40–48. I first became exposed to the Matthew (lion) – Mark (ox) – Luke (man) – John (eagle) scheme for which I argued from the sidebar on pp. 1176–7 of The New Open Bible, Study Edition (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1990) as credited on my p.44. While writing these present endnotes I became aware of David Alan Black’s book Why Four Gospels? (Gonzalez, FL: Energion, 2001, rev. 2010) that argues for the same Gospel order, and proposes an historical explanation how Mark’s lack of an introduction and conclusion makes it lean outward upon Matthew and Luke, as I independently noted on p.48 of the 2016 second revised edition of my book. Another book I also discovered only weeks before that which defended the same scheme of the Gospels is Arthur W. Pink’s much earlier 1921 book, also entitled Why Four Gospels? (see note [39] following.)

39.^See Irenaeus, Against Heresies, III. 11. 8. Irenaeus’ suggestion that the fourfold gospel is not just a historical fact but a logical necessity—based on his observations about the four cardinal direc-tions, the “four winds,” the four-faced cherubim of Ezek. 1, and the four “living creatures” of Rev. 4—is critiqued in “The Fourfold Gospel” by Graham Stanton, New Testament Studies 43 (1997), pp. 317–346. Stanton shows that the idea of the “fourfold” gospel preceded Irenaeus, and apparently emerged in tandem with the church’s adoption of the codex, instead of the less convenient scroll, the former being the perfect size to hold four Gospels. However, he points out this was not simple cause and effect, because there really are just four historical Gospels that have a faithful doctrine of God the Creator, continuity with the Old Testament Scriptures, and an orthodox Christology, and that fact could have influenced the adoption of codices, rather than the other way around.

Stanton, however, does not “like” Irenaeus’ appeal to fourfold structures in creation, which he claims were also important to the Valentinians (one of the heretical sects Irenaeus was opposing).

Another scholar, Harold W. Attridge (“Christianity from the Destruction of Jerusalem to Constantine: 70–312 C.E.” in Hershel Shanks (Ed.), Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, 2nd Ed. [Wash. D.C.: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2011, p.195]) finds Irenaeus’ arguments for exactly four Gospels “highly artificial,” mocking his associating them with “the four figures of Ezekiel’s visions (lion, calf, man, eagle.)” Nevertheless, Graham Stanton ends his article by saying Irenaeus should have cited instead the four rivers of Paradise going out from one source to water the whole earth, as he says Hippolytus, Cyprian, Victorinus of Pettau, and in our times Schnackenburg have. I personally have cited his “four rivers,” but see the fourfoldness of Ezekiel’s cherubim, the great sheet Peter saw, and the four living creatures around God’s throne—and, indeed, the “pattern” of Ezekiel’s Temple—as also being Divinely sanctioned images of heavenly realities behind earthly appearances, and not gnosticism.

My limited study of the Valentinian heresy has found no similarity to the true gospel. D. Jeffrey Bingham’s book Irenaeus’ Use of Matthew’s Gospel in Adversus Haereses (Louvain, Belgium: Peeter’s, 1998, pp.40–41) provides Irenaeus’ rationale for distinguishing between gnostic and orthodox number symbolism, which I find to answer objections of inconsistency in Irenaeus’ approach. Irenaeus says the Valentinians “form concepts of the heavenly from the Creation, rather than understanding that the heavenly gives substance, meaning, and unity to the diversity of the Creation.” Their numerology is ultimately arbitrary, because it originates in their mathematical speculations, which they then project onto the invisible spiritual world of the gnostic Pleroma. “Rather than linking their numbers to the Pleroma the heretics should link the numbers and created things to ‘the fundamental doctrine of the truth’”—meaning, for Irenaeus, what is revealed in Scripture. “Numbers do not arbitrarily derive a

doctrine,” Bingham writes (characterizing Irenaeus), “but a doctrine derives and gives meaning to numbers.”

While preparing this footnote I discovered Arthur W. Pink’s Why Four Gospels? (Swengel, PA: Bible Truth Depot, 1921). In addition to the four rivers of Eden, Pink also finds justification in the completeness of the four distinctive roles in which Jesus is presented in the accepted Gospels: Jesus as the Son of David and King of the Jews (Matthew), as the Servant of YHVH (Mark), as the Son of Man (Luke), and the Son of God (John). (This happens to be the scheme I defended in my 2013 book cited above.) He also mentions the four golden posts supporting the tabernacle’s cherubim-adorned veil, (Ex. 26. 31–2) and their association thereby with Ezekiel’s cherubim and the four living creatures of Rev. 4.

40.^See my Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework, pp. 40–48; my downloadable shorter article, “The Four-Fold Geometry of Ezekiel’s Temple” (in preparation); and my Sacred Spaces: Post- Modern Architecture and the Christian’s World-View, 1987 (self-published book, presently out of print.) For photographs of the Roman camps around Masada, see Biblical Archaeology Review, July/Aug. 2014, pp.31, 34–5; and Sept./Oct. 2018, p.36.

41.^For the dispensational view of the necessity of a coming physical structure see, for example, Randall Price, The Coming Last Days Temple (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 1999). For counterbalancing arguments, see my Ezekiel’s Temple: A Scriptural Framework, pp. 51-55; and my downloadable shorter article, “When Will Ezekiel’s Temple Be Built?” (on the Free Articles page of my www.EzekielsTemple.com website). The Ryrie Study Bible (Chicago: Moody Press, 1978, p.1289) says of “symbolic” interpretations of Ezekiel’s temple, “If it is a description of God’s relation to the church, then it is so symbolic as to be meaningless.” The New Scofield Reference Bible (NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1967, p. 884) says of the “claim that the picture is one of the Church and its blessings in this age,” that “this view does not explain the symbolism, nor why large areas of Christian doctrine are omitted.” My studies have been intended to address those objections.

42.^In my opinion, over-objectifying the chariot vision leads to great difficulties of interpretation. For example, when Ezekiel reports “seeing” the Divine Presence on the chariot, should it not at that moment be sheltered between the gold cherubim in the Holy of Holies of the First Temple, which was then still standing back in Jerusalem? The departure of God’s Glory from that temple is yet to be prophesied in Ezekiel’s book. In other words, Ezekiel is only seeing a “vision” of God’ Glory, not God’s Glory itself. Forgetting this causes many seeming contradictions in interpreters’ expositions of details like the “gleam” or “chashmal” (1.4), the “expanse” or “firmament” above the cherubim (1.22), and of course the famous “wheels,” leading them into complex, truly gnostic-like speculations about angelic realms above (something warned about in the New Testament in Col. 2:18). Rabbi Eisemann (p.74), following Rashi, well observes that Ezekiel was seeing a “blurred, inexact vision,” as if through a “speculum,” or mirror. But the temple of chs. 40–48 was seen by Ezekiel in a vision also, and in my appraisal, over-objectification of that vision has led to the interpretative “maze” discussed in my Part 3.

Copyright 2018 by Emil H. Henning III. Properly credited quotation or copying of this paper and its diagrams is allowed, in whole or part, for free, non-commercial purposes, in print or electronic form. No portion may be altered or incorporated into any print or media product offered for sale or used for any promotional purpose, without author’s written permission. Unless noted, Bible verses are quoted from the King James Version (some words modernized.)